On December 7, 1972, floating 28,000 miles above the surface of the Earth, the crew of Apollo 17 snapped the photo that would become known as “Blue Marble.” This photograph — a simple shot of the Earth — would fundamentally change the way humans saw themselves and their place in the universe. That’s what going to space can do. And that’s what taking a picture can do: it can change things. The power and significance of both these endeavors is at the heart of the spectacular new short film, Others Will Follow, written, produced, and directed by Andrew Finch.

“Films are one of the best ways to show things from a new perspective,” Andrew told us. “That’s the reason the Apollo missions resonated so much with us. For the first time, we saw our home as a tiny ball in space. We knew it was that way, but we didn’t have that perspective before. All it took was a single photo.”

We recently talked to Andrew about the four-year process of making his film, his DIY approach to production design, and why making films is worth all the effort.

How did your film Others Will Follow start?

It started when I stumbled across a speech written for Richard Nixon to give in the event that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin got stranded on the moon. It was fascinating — not only because it was never used, but because it had great imagery and sentiment in it. So I thought I could use it against backdrop of a Mars mission that ends in disaster but still serves to inspire the next generation. I started writing, and I went through a lot of revisions before ending up with Others Will Follow.

What were some of the revisions?

Well, I’ll just say there were aliens at one point.

But once I settled on a script, even though it took four years to make, I pretty much followed the script exactly. I did end up adding some shots for clarity reasons, but fortunately I didn’t have to rework much. I would sometimes spend three months on a single shot, so a bad call would have resulted in a huge waste of money and time.

So were you working on this at night and on the weekends?

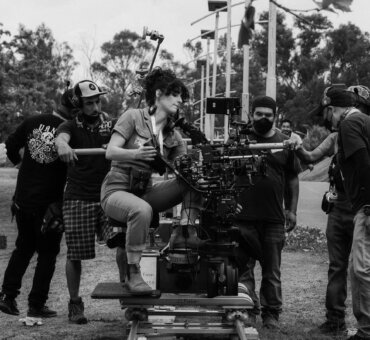

Basically, yes. I rented a workspace and started building all the things I knew I would need. The suit. The ship. I was going three or four days a week to this workspace while I was building. Sometimes I would take some time off, or I’d switch and build VFX assets for a while. It got overwhelming at times, thinking of how much there was left to do; but I’d gone too far to turn back.

Were you pretty confident it was working the whole time?

I was very concerned it wouldn’t come together, even though I had no real reason to think it wouldn’t. I was getting all the imagery I needed. But it was hard to tell if, when I put all the pieces together, the film would actually work. And it didn’t at first. There were a few surprising things people didn’t understand after the first cut, which I had to go back and fix.

Like what?

Some people didn’t understand that the astronaut was taking a picture of a Martian sunrise. Some thought it was an alien or something. I didn’t want to alter the shot to look more like an Earth sunrise, because the point is that a sunrise looks different on Mars. So I added a shot of the character on Earth looking at an Earth sunrise right before we see the Mars sunrise, so people would connect the two visually. It was a lot of stuff like that, clarifying the visual syntax.

The production design is so good. Did you have experience building sets and props?

I’d built a couple of miniatures before, but nothing with this level of complexity. And I’d never built a set. I knew I couldn’t afford to pay for the level of quality I needed, so I started going for it. I had the general form in my head for what I wanted to build, and I knew I needed a few primary components. But since I didn’t really know what was possible, I knew I had to adapt the design as I learned. So it ended up being a kind of production design improvisation. I would build a critical piece and let the actual dimensions of that define the design of the next. It’s probably impossible to work that way in a big-budget context; but I was working alone, so I didn’t have to validate my ideas with anyone else. It’s surprising how well that approach worked, but I don’t recommend building a real spaceship that way.

I based the overall ship architecture on Mars mission proposals from various space agencies that I found online. A lot of the appearance of the hardware was inspired by the Apollo command module. The interior was heavily influenced by the space shuttle. I even found some detailed schematics of the space shuttle avionics in a book, which I reworked and etched onto acrylic for the backlit panels. And the suit… I modeled that mostly on the Apollo A7L suit but I made it less cumbersome, and I wanted it to have a high-altitude feel to the helmet.

Where do you get the pieces for something like that? Radio Shack?

I wish they had this stuff at Radio Shack. No. At first, I’d hoped to buy actual aircraft panels and avionics, but it turns out they don’t look very good. And also, you can’t just buy the panels. You have to buy the entire mechanism, which costs like $6,000 for one little instrument cluster. So that was out. I ended up painting some acrylic and using a DIY CNC engraver machine to trace the reworked shuttle avionics schematics that I’d found in that book. That, combined with some LCD screens, produced the majority of the backlit paneling. For all the switches, I used little white eraser heads. Like the ones you can stick on the end of a pencil. I used 200 of them. It was pretty tedious.

At what point during all of this did The Martian come out?

[Laughs] It came out in the middle of everything, and I was very upset. That film and Gravity and Interstellar and Arrival… everybody started making realistic sci-fi all of a sudden. I sort of took inspiration from each one as they were released.

Why do you think our attention has turned to space again?

I think NASA’s termination of the shuttle program with nothing to take its place made it very clear to people that we aren’t progressing anymore. Jump-starting public interest in space became something of a cause for people like Elon Musk and Neil deGrasse Tyson and, apparently, lots of major filmmakers in the last five years…. I made the film partly because I noticed that nothing significant space-wise had happened in my lifetime. There have been some scientifically significant things, but nothing that kick-started a generation the way the Apollo missions did.

You spent years on this film. What do you think makes a project worthwhile?

For me, I’m very drawn to unique science-fiction concepts that aren’t just a backdrop for a story but are dealt with directly. Films like Arrival, where the science-fiction idea is at the heart of the narrative. I’m not as interested in interpersonal drama as I am in ideas and visual experiences. Movies, and sci-fi movies in particular, are good at those things.

Sci-fi implicates all of us. It’s saying, “Here’s where we’re all going unless something changes.”

Yes, I guess sci-fi is all about extrapolation, so it can definitely be used to warn people about undesirable futures. But I think perhaps more interestingly, it can be used to point out new ideas and perspectives, and explore desirable futures as well. It’s also a lot of fun to watch characters deal with some fascinating situation.

What’s the point of making films?

I make films because I refuse to dance… so I guess it’s a form of emoting. Films are one of the best ways to show things from a new perspective and convey an experience. That’s the reason the Apollo missions resonated so much with us. For the first time, we saw our home as a tiny ball in space. We knew it was that way, but we didn’t have that perspectivebefore. All it took was a single photo and the knowledge that a human took it. I think movies can do something similar. They can present things we know in a way that we haven’t considered them before.