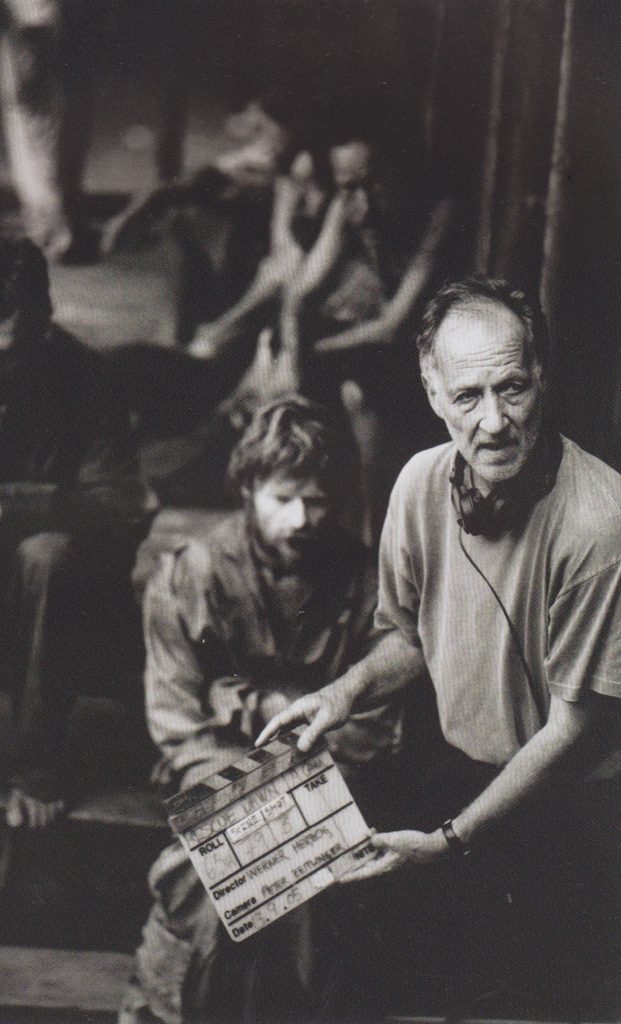

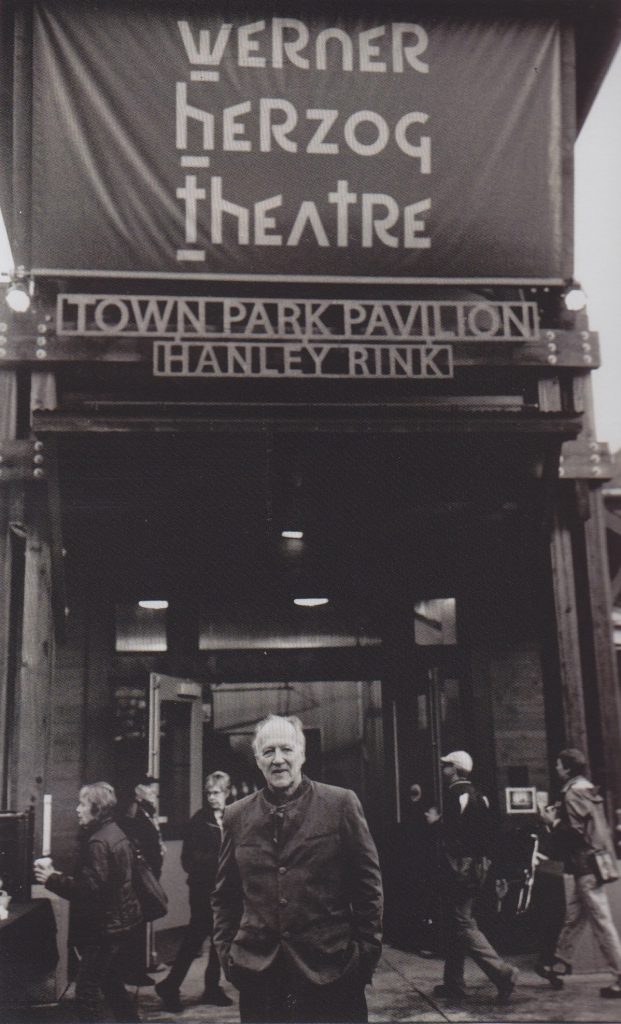

Recently, we’ve been consumed with A Guide for the Perplexed: Conversations with Paul Cronin, a nearly 600-page conversation between the legendary (and infamous) filmmaker Werner Herzog and editor Paul Cronin. While Herzog comes from an older generation of filmmakers, his rogue approach to cinema strikes us as being particularly timely today. Not just timely, actually — but challenging. At 72 years old, Werner Herzog is still ahead of his time.

Here are a few things that set our brains on fire.

Herzog on Real-Life Experience

“I always knew film school wasn’t for me,” Herzog says. “I had no formal training nor had I worked as someone’s assistant. My early films came from my deepest commitments; I never had much of a choice. It will never be the curriculum of a traditional film school and access to equipment that makes someone a filmmaker. Who wants to spend four years on something a primate could learn in a week? What takes time to develop is your personal vision.”

In place of academic thinking, Herzog is interested in real-life experiences — filmmakers who have done their time in the world, spent a few nights on the street, worked as a bouncer at a night club. Asked to describe his ideal film school, Herzog dreams that students would be allowed to apply only after they had walked, alone, from Madrid to Kiev — 2,000 miles. “You would learn more about filmmaking during your journey than if you spent five years at film school. Your experiences would be the very opposite of academic knowledge, for academia is the death of cinema…All that counts is real life.”

One reason Herzog believes real-life experiences are so important is because it’s the only type of knowledge we truly retain. “Everything we’re forced to learn at school we quickly forget, but the things we set out to learn ourselves — to quench a thirst — are never forgotten, and inevitably become an important part of our existence.”

“Maybe the answer lies not in how we make films, but instead in how we choose which films we make. ”

Herzog On The Mystery Of Filmmaking

We recently wrote an entire post on what makes films “work,” and in the end we decided it’s a mystery. Herzog seems to agree with us: “I don’t think I could ever put my finger on what constitutes true poetry, depth and illumination in cinema,” he says. The mystery remains. But maybe the answer lies not in how we make films, but instead in how we choose which films we make. Herzog: “I could never make a film — fiction or non-fiction — about someone for whom I have no empathy, who fails to arouse some level of appreciation or curiosity.” A brilliant filmmaker isn’t someone who can tell any story; a brilliant filmmaker is someone who knows which stories to tell and then trusts her instincts to tell them.

“There is never some philosophical idea that guides [my] film[s] through the veil of a story. All I can say is that I understand the world in my own way and am capable of articulating this understanding through stories and images that are coherent to others.”

Herzog on Financing

“That should be a lesson to filmmakers today with inexpensive digital technology at their disposal. You only need a good story and guts to make a film, the sense that it absolutely has to be made…Don’t wait for the system to finance such things. Rob a bank if you need to. Embezzle if necessary.”

Herzog On Writing

Herzog writes fast — very fast. In one section of the book, he recounts a time when he had to fire an actor from a film but, later on the phone, promised they would make another film together.

“What film?” the actor said.

“I don’t know yet,” Herzog said. “What day is it?”

“Monday.”

“By Saturday you will have the screenplay.”

That film was Stroszek, which Herzog considers to be one of his finest. But it’s not that Herzog is able to write well in spite of these ridiculously short deadlines. He would say it’s precisely because of his frantic creative pace that his scripts come out so well:

When I write, I sit in front of the computer and pound the keys. I start at the beginning and write fast, leaving out anything that isn’t necessary, aiming at all times for the hard core of the narrative. I can’t write without that urgency. Something is wrong if it takes more than five days to finish a screenplay. A story created this way will always be full of life.

Herzog On Lock Picking

“A crucial skill.”

Herzog on Forgery

“Carry a silver coin or medal with you at all times; if you put it under a piece of paper and make a rubbing, you can create a kind of ‘seal.’”

Herzog On Why We Make Films At All

An important question — maybe the important question — and one that doesn’t get asked often enough is “Why do we make films at all?” Beyond our creative compulsion, what value do films have in the world? We believe this is an especially crucial question to ask at a time when more films and videos are being created than ever before. (One hundred hours of video are being uploaded to YouTube every minute.) Is the backbreaking effort involved in creating a truly great film worth anything beyond a few minutes of entertainment? Herzog thinks so, for at least two reasons. First, films help guard against loneliness:

Occasionally — perhaps only a dozen times throughout my life — I have read a text, listened to a piece of music, watched a film or studied a painting and felt that my existence has been illuminated…I instantly feel I’m not so alone in the universe. Watching one of my films is like receiving a letter announcing you have a long-lost brother, that your own flesh and blood is out there in a form you had never previously experienced.

And second, films guard against chaos:

We live in an era when established values are no longer valid, when prodigious discoveries are being made every year, when catastrophes of unbelievable proportions occur weekly. In ancient Greek the word “chaos” means “gaping void” or “yawning emptiness.” The most effective response to the chaos in our lives is the creation of new forms of literature, music, poetry, art and cinema.

Herzog On Everything

About halfway through the book, there is a paragraph we can’t get out of our heads. It’s a manifesto. Or maybe it’s a provocation — for filmmaking and for living. In any case, it’s the perfect quote to close out this post. If you’ve skimmed through the previous quotes, we encourage you to read this one in its entirety. And slowly.

Always take the initiative. There is nothing wrong with spending a night in a jail cell if it means getting the shot you need. Send out all your dogs and one might return with prey. Beware of the cliché. Never wallow in your troubles; despair must be kept private and brief. Learn to live with your mistakes. Study law and scrutinize contracts. Expand your knowledge and understanding of music and literature, old and modern. Keep your eyes open. That roll of unexposed celluloid you have in your hand might be the last in existence, so do something impressive with it. There is never an excuse not to finish a film. Carry bolt cutters everywhere. Thwart institutional cowardice. Ask for forgiveness, not permission. Take your fate into your own hands. Don’t preach on deaf ears. Learn to read the inner essence of a landscape. Ignite the fire within and explore unknown territory. Walk straight ahead, never detour. Learn on the job. Manoeuvre and mislead, but always deliver. Don’t be fearful of rejection. Develop your own voice. Day one is the point of no return. Know how to act alone and in a group. Guard your time carefully. A badge of honour is to fail a film theory class. Chance is the lifeblood of cinema. Guerrilla tactics are best. Take revenge if need be. Get used to the bear behind you.

Trust us, we could go on and on. A Guide for the Perplexed is unlike any other filmmaking book we’ve ever read. It’s a huge mess of thoughts, recollections, arguments, rants and philosophies. It contradicts itself, repeats itself, corrects itself. It is the exact opposite of a typical filmmaking “how-to” book. There are no easy answers. At one point, Cronin asks Herzog if there are any rules in filmmaking, and Herzog responds by explaining why a cowboy would never eat spaghetti. The book wants you to interpret it, disagree with it, throw it out the window if need be. And when you finally get to the end, rather than becoming an imitation of Werner Herzog, you’ll find that you have become a more pure and braver version of yourself. Which is, of course, the most Herzogian thing you could do.