In his or her own way, almost every person in the world is a travel filmmaker. When people find themselves in new places, they get out their camcorders and hit Record. These videos, of course, are historically some of the most boring videos ever made. That’s why when a professional travel filmmaker like Brandon Li turns his eye on a place, the result is so striking. There is an art to making a great travel film, and we hoped Brandon could teach us what it is.

As a former MTV producer and a current vagabond artist, Brandon is something of an expert at both filmmaking and world traipsing. And he’s found a way to put the two elements together. He told us, “[I realized] I could just go out and live and do cool stuff and film it and make stuff that people would actually want to watch because it’s actually interesting stuff.”

For anyone who thinks that sounds like a pretty decent life (count us in), read on. Brandon Li has a few things to teach you.

What are you doing in Abu Dhabi?

I’m shooting some promotional videos for Etihad Airways, which is Abu Dhabi’s airline. They’re coming out with some new planes, and I’m filming little walk-throughs on the planes, showing all the features of first class and business class, that kind of thing.

Is that pretty cool?

For me, it’s basically just a paycheck. It’s not my passion. I don’t entirely support the whole ultra-luxury lifestyle. These planes have apartments on board for $20,000 a flight. One way. You get a butler all to yourself.

That’s pretty sweet.

I guess. But the thing about Abu Dhabi and Dubai is that without technology, they basically don’t exist. These places have nothing cool that isn’t artificial. You take away the artifice, and you have a desert. And not even a nice desert. Everyone here is so accustomed to luxury because without it, you basically have nothing. You become numb to it.

Have you always been such an active traveler?

I lived in Missouri until I was 18. I couldn’t wait to get out of there because most of my friends were planning on becoming real estate agents or nurses, and I didn’t want to be either. Throughout my childhood I was always making short films with my friends. I always knew I wanted to be a filmmaker of some kind. So I ended up going to film school — basically the only one that accepted me: University of North Carolina School of the Arts.

It was a good film school. It taught me the traditional methods of filmmaking. As soon as I graduated, I started working for MTV on a show called True Life.

What was that like?

The way True Life worked was they’d give you an assignment, and you’d go out and film the thing yourself, edit it yourself, and basically make an entire TV episode with just a camcorder and a couple lavaliers.

They just sent you out to follow somebody around?

They’d give me a topic and an American Express Gold Card. They’d say, “Hey, your topic is narcolepsy. See you in six months.” They’d give me some leads but they always sucked. The problem is, when you’re filming a reality show like this, it all depends on what is happening right now. Usually the interesting story had already passed by the time I got the lead.

So how did you find stories then?

A whole bunch of ways. Craigslist was usually the starting point. I’d put an ad either in “Gigs” or “Jobs,” someplace that had a wide spectrum of people seeing it. Then I’d interview hundreds of people. That was one way. If a show was about, say, narcolepsy, I might call up clinics and ask doctors to suggest it to their patients. That worked a few times. Then there was a website called, I think, ExperienceProject.com. It’s like a social network for people who want to talk about their personal issues. Or sometimes I would find stories through friends.

Were there skills you picked up that are still useful to you?

True Life is where I learned to do documentary-style stuff. Before True Life, I had no interest in anything real. I just wanted to make comedy videos. Then I did True Life, and suddenly I was much more interested in real stuff. And in traveling. While I was doing True Life, I was generally in a different city every two weeks for eight years.

Were there any lessons you learned about what makes a good documentary story?

I learned a lot about how to catch conflict on camera. I learned to smell trouble and put the camera in the right place. But maybe the most important thing I learned was how to construct a story spontaneously. Just little storytelling things, like keeping the audience spatially oriented. You want people to know where somebody is going, what they’re doing, eyelines, reaction shots, things like that. Just the bits and pieces of a scene that we’re familiar with from narrative cinema. You need those same pieces even if it’s a completely unplanned documentary. I learned how to gather all those bits and pieces. To actually shoot scenes.

I also learned how important it is to have a point of view. If I’m at a festival where there are 1,000 things going on, I could either spend my time getting random shots of every single thing I can, or I can pick a point of view and stick with it. I can decide, “Okay, I’m going to tell this festival story from the point of view of, say, the guy who breathes fire.” So then I’ll focus on how the festival feels to him. Or maybe from the point of view of a child who is experiencing this for the first time.

I can see that in Gateway to the Ganges. It feels like much more than just random travel scenes.

I wanted to profile these holy cities that weren’t as well known to the outside world. I wanted to show it from the point of view of people who live there and struggle there day after day. What shocked me about India was how much poverty is everywhere. Most people are straight-up living in houses made of sticks, walking through fields of trash every day. I wanted to show the balance between the suffering that happens there all the time and the rituals and ceremonies they use to strengthen their faith and get through their difficult lives.

So what was your process like for making a film like this?

I spent a lot of time chatting with whoever could speak English…café owners, merchants, just asking them, “Hey, so you live here. What’s it like? What do you do? What is a regular day like? What should I see?” I became good friends with this guy who owned a café, and one morning I ended up on a scooter with him, riding up the mountain. The café owner told people what I was doing, told them not to smile for the camera, to just ignore me. Then this one guy, as soon as he heard I was filming, he grabbed two sickles and started climbing a tree. I realized he was hacking off branches to feed to his cattle. They existed in this balance where they could only have so many cattle because they only had so many trees. It was interesting to see them living on the limits of subsistence.

How do you condense an entire place into a three-minute video?

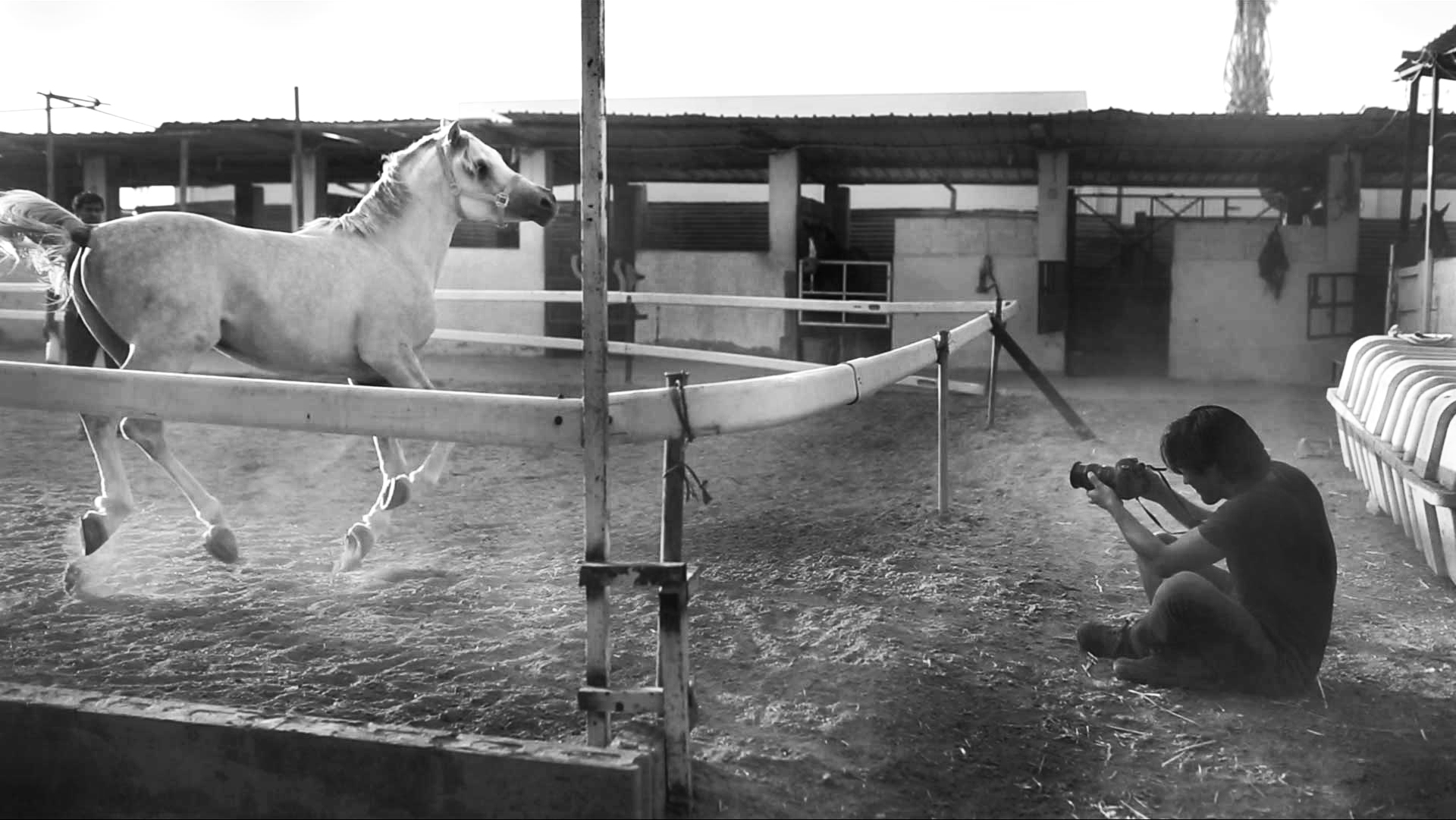

Mainly, there are two things I look for. One is what’s unique about the place. What’s something you can’t find anywhere else on the planet, or at least anywhere else outside of that country? That’s the first thing. The second thing I look for is movement. I’m shooting video, not taking pictures; so something has to be moving inside the frame. It’s surprisingly difficult to find stuff that moves when you’re shooting travel films. Most sightseeing is organized around static things: buildings or mountains, which are beautiful, but they don’t do anything. It’s hard to make them work for video.

I also try to get as intimate with people as possible without violating their sense of privacy, and I try to do it as quickly as possible because I like to cover a lot of ground when I’m shooting. It’s always a delicate balance of reading the subject’s comfort level while getting closer and closer to them. I prefer people to be unaware of the camera. I like to keep the fourth wall up.

My pet peeve in travel videos is the little kids in Africa smiling and chasing the camera, running up and making goofy faces. I think Westerners misinterpret that footage to be like, “They’re in some idyllic village where life is simpler than ours and they love it.” They’re not. They’re just happy because a camera is there. It still sucks to be poor.

How important is it to plan ahead?

Here’s how I look at it. If I’m going somewhere, I have to have a climax in mind for my video. I have to have something visually kinetic that is interesting and moving and unique. Beyond that, I don’t schedule a whole lot.

With Gateway to the Ganges I knew I wanted [people] bathing in the river, and I wanted the fire ceremony. I knew those two things would be really interesting on camera. Lots of motion, lots of emotion, and both said a lot about the area. Beyond that, I just wandered around. I’m always after something spontaneous. I try to capture something you can’t possibly plan. I think that’s what makes videos really interesting.

That’s a tough assignment.

Yeah, but the thing about spontaneous moments is they usually repeat. For instance, there’s a shot in there of a monkey jumping. I spent 15 minutes trying to capture the perfect jump in slow motion and missed most of them. So I usually look for things that have some sort of repetition. Even bathing in the river. It looks spontaneous, but actually those people kept dunking themselves and coming back out. I had four or five tries per person.

The funny thing is that most of this is stuff I learned while shooting True Life. I was always trying to capture spontaneous moments on that show.

Has traveling so much changed your perspective on being a filmmaker?

I’ve realized you just have to go do things. I had such a hard time coming up with things to film when I was living in Los Angeles. It would always be some contrived situation about some guy who thinks his girlfriend is a ghost or something. Like, “Wouldn’t that be weird if your girlfriend were a ghost?! Crazy, right? There are twists!”

Then people get involved and micromanage the script, like, “I don’t know if I’m really feeling that twist in the third act,” or “It feels a little too cliché, a little too repetitive, a little too…whatever.” I could go through all that, or I could just go out and live and do cool stuff and film it and make stuff that people would actually want to watch because it’s actually interesting stuff.

You don’t have a hard time coming up with ideas anymore?

No. Now I’m just filming the world. And the world is pretty big. Every corner you go around, there’s something interesting.

One of the things we appreciate most about Brandon is not just the fact that he’s an excellent filmmaker, but he’s a very thoughtful one too. When you talk to Brandon, it’s obvious he’s thought a lot about what he does and why. So in addition to the practical lessons Brandon shared above, another lesson we can take away is the value of contemplating your craft. Understanding why you do the things you do. The value of thoughtfulness itself.