If there is no “right way” to make a film, then is there no “wrong way” either? If you’ve seen Paul Özgür’s work — an award-winning Dutch cinematographer whose films have screened at festivals like Sundance and the Berlin International Film Festival — you’ll start to question if there are any boundaries at all. “This is filmmaking,” Paul told us. “There are no rules.”

This is the kind of attitude that not only made Paul a nightmare for his film school professors (“They kicked me out because I had a massive ego, according to them”), but also makes him such a fascinating cinematographer to watch today. His films are raw, purposefully inconsistent, and undeniably beautiful and moving. He is a cinematographer with vision and — maybe more importantly — bravado. A filmmaker who doesn’t follow the rules.

Here’s Paul Özgür on film school, working with directors, and his most useful tool on set: a piece of string.

Oz-ger?

I don’t even know how to pronounce it in English. It’s probably like “Ooze-gur.”

Ooze-gur. Got it. Should we call you a cinematographer?

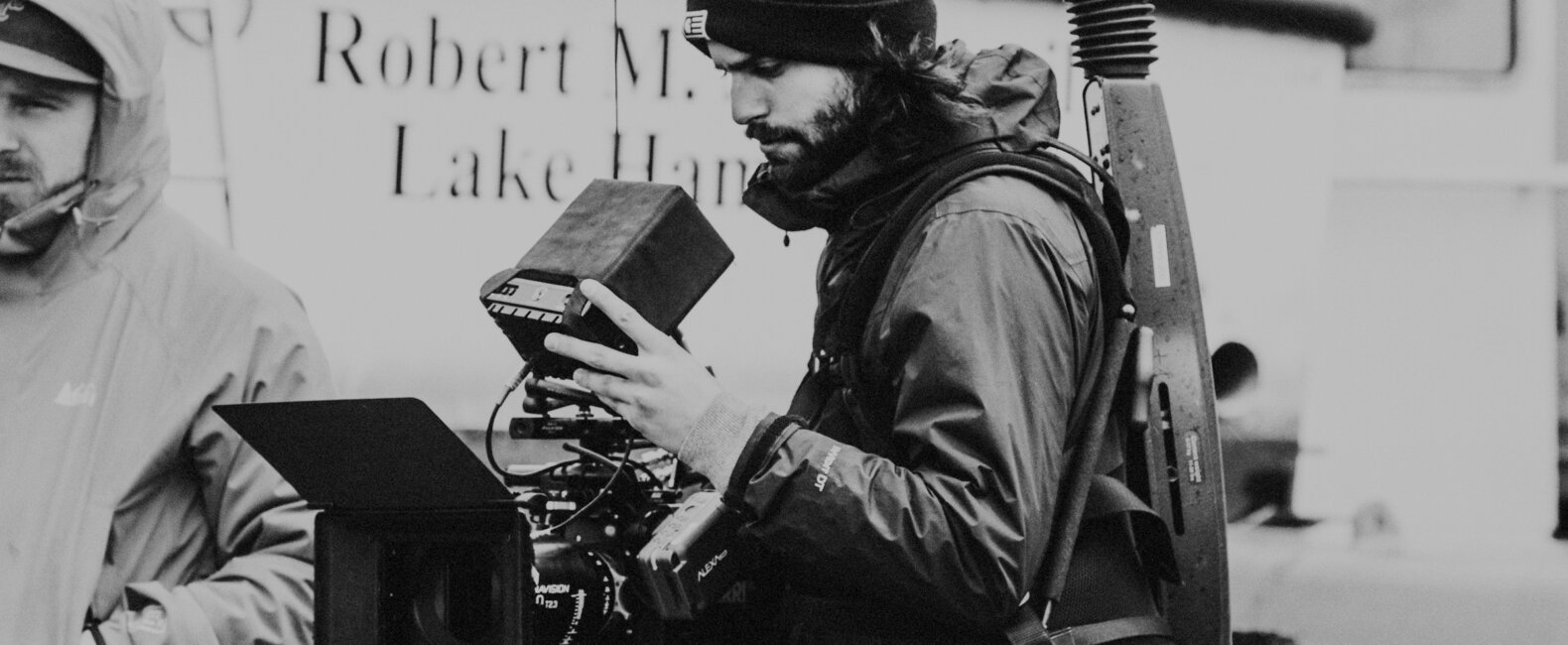

That’s what I call myself. In the U.S. I’d technically be called a DP. In fact, my agents keep telling me to call myself that. In Holland, it’s much more common to be called a cinematographer. Usually the DP has an operator and doesn’t actually touch the camera, but I prefer to operate the camera myself. I’ve worked with operators in the past, and for some shoots I still do. But it tends to increase the number of people on set and add to the chaos. If you’re sitting next to the camera instead of behind it, there’s a certain bond you’re missing with the actors.

Why did you start making films?

To afford skateboarding, of course. When I was 14, all I wanted to do was skate. To make money skating, you need sponsors. And to get sponsors, you need videos of yourself doing tricks. So that’s how I started. I filmed my buddies skateboarding, and gradually I spent less and less time skating myself, and more time filming and editing. Eventually it just took over. By the time I finished high school, I knew I had to be a filmmaker.

Where did you study?

I applied to the Dutch Filmers Academy as soon as I finished high school, but I was rejected straight away. Probably because all I’d submitted were skateboarding videos. So I went to art school instead, where a whole visual world opened up for me. I realized, Oh, wow, it actually makes sense to explore different visual mediums. I was painting and doing all these sculptures and stuff. Then I made three short films, which were quite diverse, and I applied for film school again in Amsterdam. I got into the cinematography program straight away. It was a very practical education; but at the same time, they gave us plenty of tools to play around with.

What do you mean by practical?

I’ll give you an example of a piece of advice my advisor gave me in school. It’s a very Dutch expression, but I think you’ll get it. He said, “Just make sure you know how to put the camera on the tripod, then we’ll talk.” At the time I thought it was lame, but now I get it. You have to know your tools well to make your art.

What did you think of film school?

Film school is this sort of bubble. You’re constantly comparing yourself to other DPs. It’s very hard not to copy other people’s work. Your teachers can be very prescriptive. I had a tutor who was very much like, “You should put a camera on a dolly in this situation.” And “You should do this move in this situation,” etcetera. But I was like, “I want the camera on my shoulder. I want a long lens. I want to push the material and make it look really raw.” He was like, “You can’t do that.” And I was like, “Why not?!” This is filmmaking. There are no rules.

You’ve worked on a lot of interesting films. How do you decide which projects to take on?

Commercials and music videos are usually pretty quick to do, so those are easier to say yes to right away. With a feature, the most important thing for me is the director’s passion.

Not the script?

It doesn’t matter how good the script is. If the director doesn’t have vision and passion, the project is going to suck. The director has to need to tell the story. If they want to direct the movie just so they can be the next up-and-coming director or just to make money, I turn down the project. So, for me, the most important part of taking on a film is sitting down with the director and hearing them share in their own words why they need to tell the story.

There aren’t any big egos in the projects I take on, usually. If I don’t like a scene, I can say something. The directors I’ve worked with have been more open to my suggestions throughout. They trust me and allow for a more open-minded environment as a result. Obviously, that comes with experience, but that’s another reason why the director is so important to whether or not I decide to take on a project.

Has making films in Europe influenced you as a DP?

It’s made me much more efficient. Shoots have smaller budgets here. Instead of having the time for a hundred different takes, you’ll need to nail it in just a few. That’s part of my culture as well, you know. Holland is pretty much under water. If the dams break, we’re gone. So we have to think practically. Second of all, I think it’s helped me realize that less is more a lot of the time. For example, renting lights for shoots is extremely expensive. So instead of wasting money on that, I’ll find shots that don’t need the light. The tools are just tools — like a dolly, for instance. If you don’t have one, you don’t need one. You can figure out a way to shoot a scene without a dolly. That’s a good thing.

What’s something you use on a shoot every single day but it isn’t your typical piece of equipment?

String.

String?

Yeah! I use a hole punch on the script, and then I slip a piece of string through the holes and fasten it around my neck. I wear the script like a necklace around the set. It looks insane, but that way it’s on me at all times and I can’t lose it. I like to keep notes and diagrams on mine, so it’s nice to be able to grab it easily.

Could we get three pieces of advice for young filmmakers today?

Number one: get a website. Recently, I went back to my school and gave a talk, and almost none of the students had websites! It was insane. I have to be able to Google you and find your work. It’s the nature of this industry.

Number two?

Number two would be learn how to say no. That’s an important thing to be able to do to get where you want to go. In the short term it might be painful; but in the long term, it can help you do the stuff you really want to do.

And number three?

Make sure you know how to put the camera on the tripod. Then we’ll talk.