While ‘free will is not free’ sounds like an exhortation from Patrick McGoohan’s ‘Number Six’ character in The Prisoner TV series, it actually serves as the tagline for season 3 of HBO’s Westworld. Continuing to defy expectations and eschew easy answers, showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy have taken the characters – human and otherwise – out of the wish-fulfillment theme parks of Delos Inc. and into the (apparently) real world of Earth 2058. Developed far beyond the mechanical constructs featured in Michael Crichton’s 1973 film of the same name, the constructed ‘hosts’ featured here are more akin to the organic replicants in 1982’s Blade Runner – and are similarly capable of taking vengeance on their creators.

Director of Photography Paul Cameron, ASC, has shot over a dozen feature films, most recently 21 Bridges, The Commuter and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales, and is a BAFTA winner for his work on Michael Mann’s Collateral. Other projects behind the eyepiece include music videos for David Bowie and Janet Jackson and commercial spots for AT&T and Revlon. Cameron is the recipient of three Clio awards, including one for the memorable BMW short promotional film Beat the Devil.

He earned Emmy and ASC nominations for his work on Westworld’s pilot, and at the request of series co-showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, returns this season to lens the first episode [Parce Domine] and direct the fourth [The Mother of Exiles.]

Musicbed: Had things changed significantly on the series since your earlier involvement?

Paul Cameron: Jonathan and Lisa, the writers and creators of Westworld, explained the show’s new arc, and what it would mean to leave the park setting and see things in 2058. It was very similar to the original pilot in some ways, because again we’re figuring out a new world in terms of what it looks like and where it would be shot. When you put a show like this together it’s really a meeting of minds between showrunners, the design team and all aspects of production, because there are so many ingredients that have to be realized fully to complete the vision. Jonathan and Lisa are looking for professionals who can bring more than just their past experience; there has to be something fresh as well.

One way Westworld has set itself apart from most other shows is through shooting on 35mm film. Did that continue in season three?

It’s an absolute pleasure to be on film again with Westworld, though it wasn’t without difficulties. Finding experienced film loaders is one problem. We did consider whether there would be merit to shooting digital this season since it takes place in a different world and time frame. I discovered from engineers during testing that there is a pretty extreme tradeoff in color rendition when using the higher sensitivity setting on digital cameras like Sony’s Venice. Whereas if you light somebody two stops under on film, even with light falling on their face, you can still see the blue in their eyes. With digital capture on the Venice or even the Alexa LF, you lose saturation because you’re not in film’s velvet colorspace. The misconception with digital capture seems to be thinking it is ‘as good as.’ It’s almost there, but testing indicates it still falls short.

We did wind up incorporating some digital with the Venice this season, mostly using wider Zeiss Supreme primes for wide shots and car chases at night – situations requiring a lot of lighting if you’re shooting film — though that call required approval from Jonathan and Lisa. Having used it for 21 Bridges, I knew the 2500 ISO setting would play well for nights, letting you dig into the exposure and even close the lens down a bit. Even in that mode, the Venice image is still incredibly clean, with just a slight bit of noise, but when you combine that with the interactive program LiveGrain during the DI, it comes pretty close to a film look. The bulk of the series was still 35mm, using Kodak Vision stocks, predominantly the 5203 [50D] and 5219 [500T] stocks, and we continued with the Arricam Lite camera, which let us shoot either three- or four-perf — along with their Studio model.

The portions of season one and two taking place within the park had to bridge between two very separate locations: a western town set at Santa Clarita’s Melody Ranch and those epic landscapes found in Moab, Utah. Is there a similar strategy at work this season?

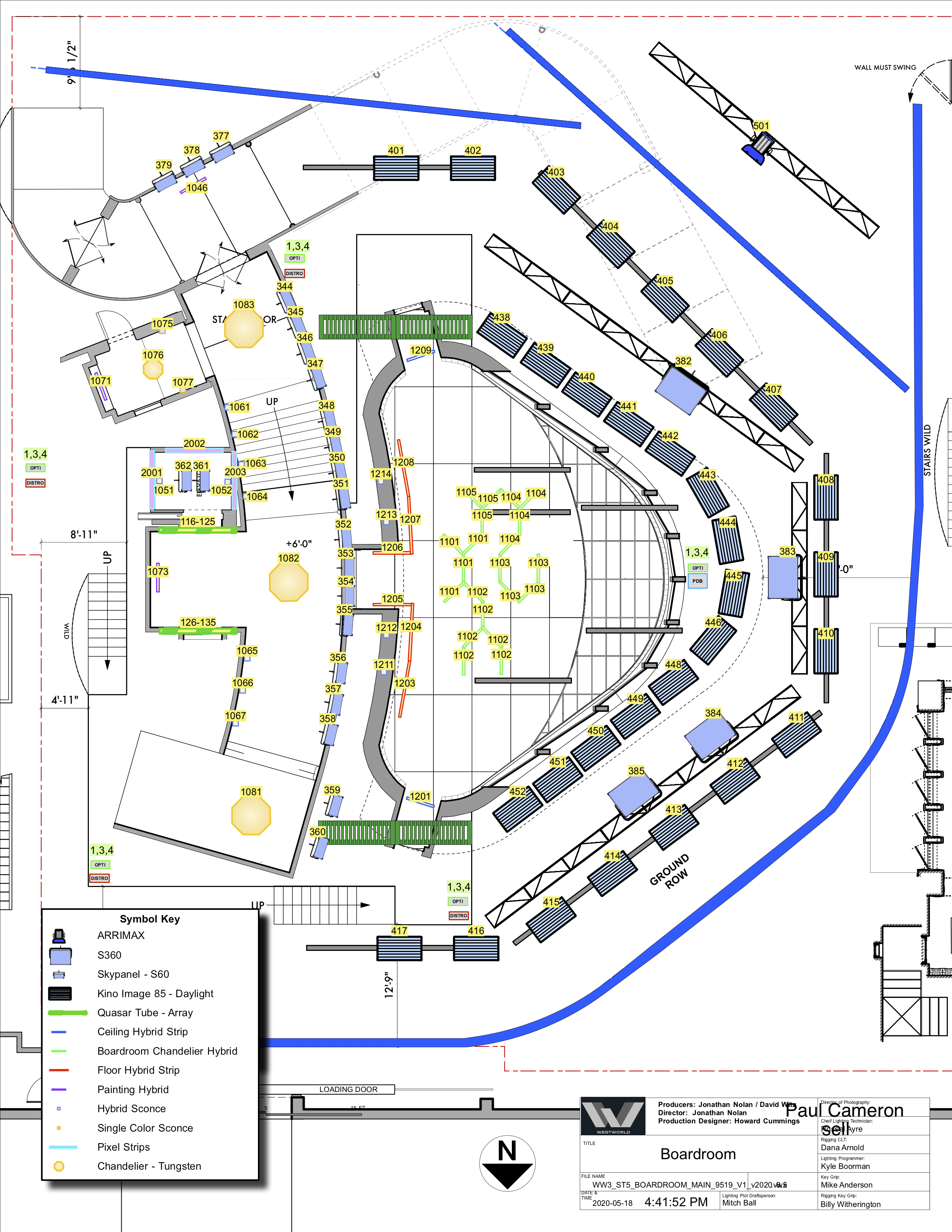

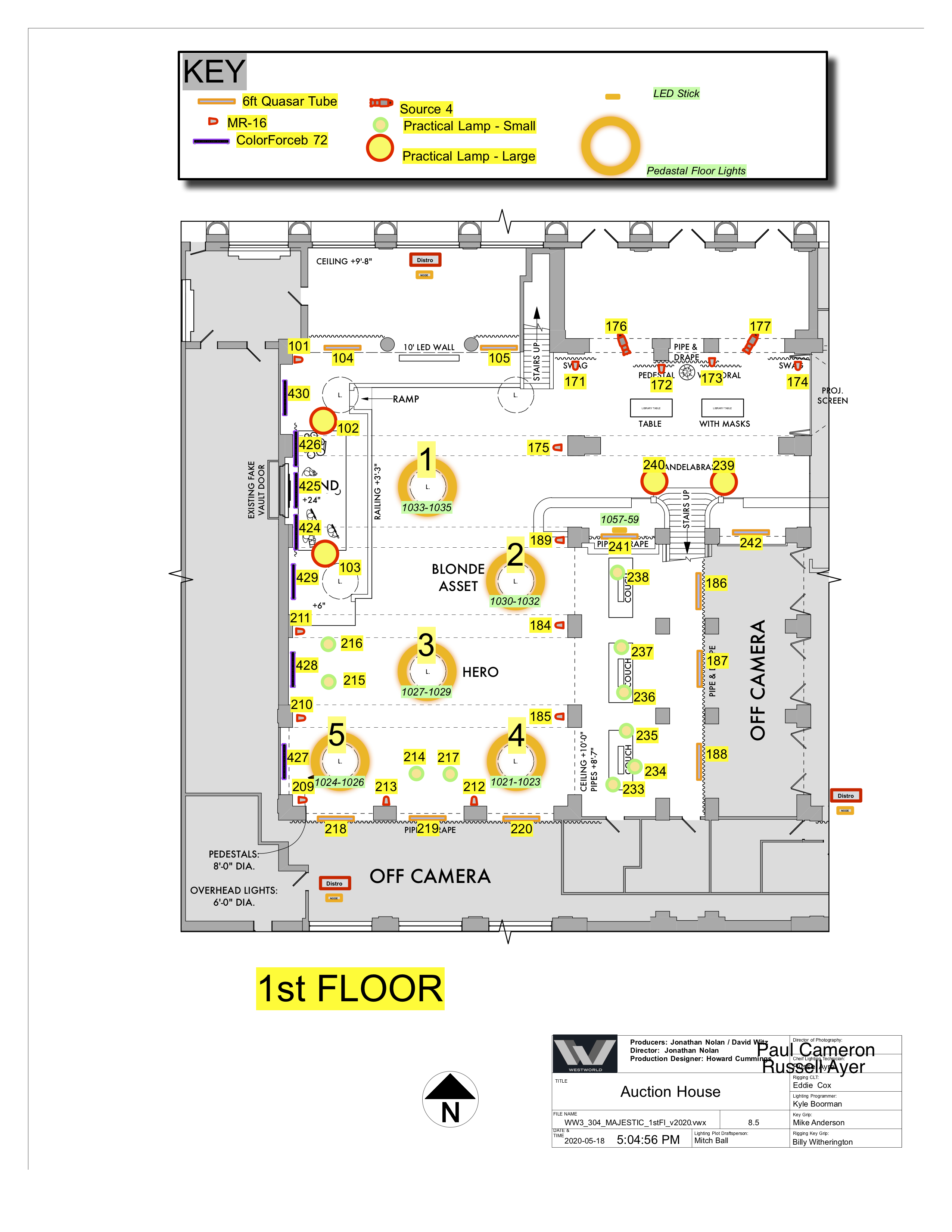

We utilized Singapore for big views of future L.A., along with a lot of strategic shooting of parts of modern Los Angeles. Spain as used for the Delos building exteriors, with sets built on stage here for the interiors. Some of those had floor-to-ceiling windows with LED walls outside, on which location plate imagery shot by myself and the other DPs got played back. As the camera followed the actors, the backgrounds shifted in real-time to show proper parallax – it was in the vein of what they did on The Mandalorian, but not full volumes. We used a lot of LED lighting on-set as well, many Arri SkyPanels, while on location, we used lightweight wireless LEDS and Fresnels.

What were the creative concepts fueling this Earth of 2058?

It isn’t Ray Bradbury or some electronic graffiti look you see in a lot of future sci-fi. You go to Singapore, where you think it is inundated by technology, but there’s a really interesting mix of forms. Skyscrapers with huge gaps halfway up, where there is a park with overflowing greens cascading ten stories down – that felt like the future, so Singapore made sense visually for our Los Angeles. While watching the premiere at the Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard, I was thinking, nobody is going to believe this place is real … even Apple wouldn’t build this!

The location shoots happened in the middle of our production schedule. That’s because of what didn’t happen last season when they planned to shoot in India. It got left too late in the schedule, so budgetarily it couldn’t happen and the scenes were shot in Pasadena. So this year, production brought some directors, including me, over for a few days in Singapore. Along with cinematographers John Grillo and Zoe, I was DPing some days, then directing nights. We also shot some nonspecific material that could be used for the later episodes, which hadn’t yet been written.

In terms of your cinematography on the series, you’ve used two cameras for much of shooting. What kinds of compromises do you have to live with when going this route?

After making multiple films with Tony Scott, I came to embrace the use of multiple cameras. Sometimes the second camera can’t get too close to the actors because of what the A-camera sees, or when we had Steadicam and dolly shots, so I’d use long lens pickups for B- and C-cameras. Even if the eyelines might not be perfect, you’re getting the excitement of capturing something as it is really happening as opposed to being restaged for camera, so there’s a life to the thing.

I read that the show uses the Pix system for digital dailies and that you arranged to get HD taps for the film cameras.

I never go into the tent, finding it detrimental to the energy found on set. Instead I look at the A-camera monitor, making my lighting decisions by eye. There’s still that piece of technology called a light meter that many DPs don’t even use anymore, but I like knowing that all of my key lights are going to be a half-stop under. In watching many DPs, they seem to light things one way, then find the reverses are too bright, so they ND it down. The meter is a faster way of working for me.

As opposed to a waveform monitor?

What’s a waveform monitor? [laughs] If I’m really concerned about a highlight, I might check a waveform two or three times in the course of a movie. There are some DITs who want you to expose the image for the best possible result, but we never did that for film and shouldn’t for digital capture either. There’s no reason you can’t beat the bottom of the IRE line or waveform; if you want to live there, it’s important DPs maintain their ground on digital capture.

If your dramatic scene in a living room has to feel like the characters are lit by practicals, you may put a softbox in the middle of the room so the general exposure runs two stops under. A DIT may come to you saying I should open up a stop-and-a-half to get it recorded correctly … which is an unfortunate translation of the situation that I feel is inappropriate, as it is the choice of the DP.

Recently you directed a short for Mercedes-Benz, and in the past helmed commercials for Prada and Cadillac, among others. What was it like taking the reins for a high-profile dramatic series?

There are twelve production days and two second unit days per episode. When I heard about what was planned for mine, I very enthusiastically began conceptualizing. Later, Jonathan and Lisa told me how the season arc had changed, so I would get more in the way of major plot revelations featuring the principal actors and less action. By the time I got a script, we had already shot Spain and were going to Singapore. The newest changes meant a lot of the locations I’d planned were now out, which called for a mental workout to change gears. I did shotlist extensively, plus doing some schematics, sketches of camera angles, and rough storyboard frame ideas. I presented these ideas to [episode DP] John Grillo and A-camera/Steadicam operator Chris Haarhoff.

Camera movements were story-dictated, though the show has established a certain style, in that we move when the characters move and try not to do too many gratuitous moves for their own sake. The show’s been blessed with Chris as A-cam throughout. We use Steadicam a lot, and when you’ve got somebody like him, you can design ambitious shots, and with a crew that knows how to pull focus accurately and under difficult conditions, that’s an awesome set of skills available to execute those shots. And the actors bring just as much professionalism.

And how do you feel about the final product, after your work in the cutting room?

You have a vision of how it is going to cut all the way through, yet it can change very drastically, often for the better. Thematically, there’s obviously a message about potential dangers with AI, but every episode provides a fuller view. When you see idiosyncratic behavior – like when Aaron Paul is sitting on a building beam eating lunch alongside a robot swinging his leg — that really helps flesh the idea out in a way that people relate to emotionally.

I didn’t initially realize the editor gets eight days before you come in, cutting to match the script. So I had four days to work, two spent tweaking the cut and the other two playing 52-card pickup with the episode’s ending, tightening up some big revelations. Jonathan liked that direction and took it even further in the final.

With Westworld already renewed for a fourth season, do you see yourself returning?

After episode four I took a week off, then shot Reminiscence in New Orleans for Lisa Joy. She and Jonathan are people you can enjoy spending 14-16 hours days alongside, and whatever they have planned for in the future, I hope to be a part of. You look at what goes into a 100-million-dollar, two-hour movie, and then see them get a whole season of material at the same price, but with more great actors and similar or greater production values. They have high expectations for visual content, so that also makes them great to work with.

For more articles with leading cinematographers like Jarin Blaschke, Chayse Irvin, CSC, Reed Morano, and more, click here.