Some projects are deceptively difficult. Nailing a performance or putting together an emotional moment can seem easy to the audience but involve late nights and hours of hair-pulling. Then, there are projects like Porsche’s Drive2Extremes that are so difficult to create, it couldn’t be more obvious. Nearly impossible, even. According to Director Nick Schrunk, taking on the challenges in a project like this is a gamble, but one with high rewards:

“Any director or creative would tell you the hardest part is trying to figure out what risk to take and when to be conservative, to make sure that you have the shots. The whole time I was supportive of the risk, but at a certain point, you have to knock this out. We were particularly successful with taking risks on this one,” he told us.

And, if you haven’t seen the film yet, successful is an understatement. Nick, along with world-renowned drone pilot Johnny FPV, managed to stitch together the most incredible drone work we’ve ever seen across two identical tracks—one in Finland, and one in the United Arab Emirates. And, they were able to capture it while battling searing heat, blistering cold, drone-destroying rocks, and ice—as well as a camera that hadn’t been introduced to the market yet. We could talk about how impressive this is, but we’ll just let Nick show you.

Here’s Director Nick Schrunk.

Could you describe the role of a director in a piece with no actors and no traditional narrative?

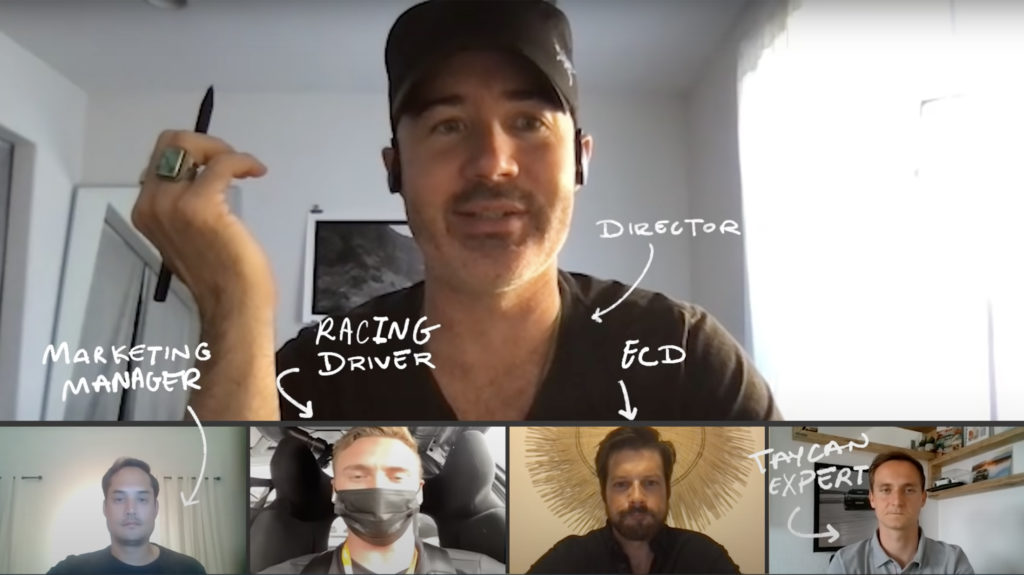

A director in this type of role—and everyone has their approach—is a master collaborator who has to create all of these systems and help people work in unison. Very rarely do I find myself as the person with the specific idea; rather, I’m the person who works with everyone to tie all of the ideas together. One thing I want to mention here is that I was collaborating nearly equally with Johnny Schaer, who goes by Johnny FPV.

Johnny was the only camera on this job, which is incredibly unusual. It puts so much pressure on one person—a director usually relies on a variety of things to tell their story. On this one, we were putting all of our eggs in one basket. We set this creative boundary at the beginning and decided we were going to work within it to create something different and new.

When you look at my role, a big part of it was creating an environment for Johnny to go and be who he is, which is the most incredible drone cinematographer in the world. But, for him to succeed, there are thousands of micro-decisions. What type of angle is the driver going to take through the corners? What kind of attack are we taking? How precise do we need to be? Are we going to be more spirited and reckless through the corners? It looks more exciting, but maybe it doesn’t show the detail of driving as much. Where does the caribou stand? Do we shoot early morning light, and does light continuity matter for this?

I wasn’t necessarily the person working with actors or the person with the specific vision. I was the person collecting all of the gems that everyone was bringing to the table, putting them together, running this so everyone had this homeostasis built around them, to do what they do best. That’s what created something I feel is very special—everyone was contributing towards something with this very specific boundary set around it.

How did you decide on the locations? “One hot and one cold” doesn’t narrow it down very much, does it?

If there are characters in this film, it’s the locations. The locations are the actors. You have these two extreme environments, both of which have their beauty and their sharp edges. You have glistening snow in Finland, but it’s bitter and cold and freezes your fingers off. In the desert, you have that golden hour of beautiful white magical temperatures and in the middle of the day, it melts you into a puddle and fries you like an egg.

It was fun to play with both of those extremes. Racing on ice is so hyper-specific for what you need out of a track, a lot of what we looked at there was what we bring in for our elements. However, in the desert, that was an open canvas. We needed to find a piece of desert that would work for driving, and also work for the visuals with a drone. It was a pretty wide brief.

We looked everywhere from Wadi Rum in Jordan, all the way through the UAE, and ended up in the Liwa desert outside of Abu Dhabi, where they shot all of the Tatooine scenes from The Force Awakens and John Wick: Chapter 3, and it’s the most incredible desert in the world. There are dunes like you’ve never seen before. We found this little swath of land with the production team, and we had to essentially survey it, making sure that we could create an exact, GPS-accurate match of the Finland track. We also needed to be able to drive on it in a way that didn’t harm the environment or cause any environmental change.

It was a pretty tall order to do all of that. The reason we picked it is that there are small dunes in between the large dunes, and there was lots of barren, flat desert for driving rally-style. You could drive through the dunes, which created foreground and depth, and also challenges for the drone. I felt it was one of the most unique things that we did. We literally built a track on the opposite side of the world without harming the environment, doing it in a way where the driver could perform well.

Did you work closely with the driver to map out the shoot?

Working with our driver, Jukka Honkavuori, was essential. There are ways you can make decisions yourself based on intuition or experience, but nothing changes quicker than when a driver shows up at the track for the first time. He takes that first lap and tells you everything right and wrong about it. He was able to come on one of the scouts, but a lot of what we did was coordinating over Zoom between photos and video, sharing references, looking at corners, talking through everything. It was an incredible amount of work.

It seems like there’d be plenty of unknowns going into a shoot like this one.

The biggest unknown was that Johnny and I hadn’t worked together before. I was very familiar with Johnny’s work, and he with mine. Funny enough, when we were doing these Zoom calls with people on the other side of the world, in Germany, Finland, and the UAE, Johnny and I had realized we’re next-door neighbors. He lives one block away from me in Venice!

We were able to do a lot of the pre-planning ahead of time in my backyard. One of the boundaries we set for the creative was that we would never use a hard edit. It would always either be a continuous movement or a hidden transition. So, instead of approaching this like a traditional commercial, where you have one storyboard for every second of film—cut from a car arm to a GoPro to a drone shot to a handheld shot—we were treating it as if there was no cutting. You have to plan your next two movements with the drone, where you’re going, or else this whole thing’s not going to work. And then for us to be able to cut between the different environments seamlessly, we had to do the same movements we did in Finland, in the middle of the desert. That’s a huge ask for a drone pilot.

So, even though we attacked it with our shot list and plan, once we get there, we were moving stuff all over the place trying to construct this roller coaster so it never hit a dead end. Part of the fun, but also part of the insanity, is that every day you went back wondering if it was working. It wasn’t apparent until you’d look at the footage. We would shoot 8-, 10-, 12-hour days without seeing a shot until we got into the edit bay that night. That’s a special type of insanity—to be able to be that confident with your plan thinking, “This is going to work.”

Did you encounter any problems with the drones?

A lot of the challenges we had to overcome on the technical side involved the extreme cold, and the extreme heat. In Finland, we’d steer the drone into the roost behind the car, or if the drone would end up crashing, and every little crevice of the camera would get packed with snow. Snow melts to water, and water is just terrible for cameras. We had a blow dryer out there for when one drone would crash.

Also, Johnny can’t wear gloves while he’s operating because it’s so precise. And, because of the radio signal, he had to be standing outside. It was 30, 40 degrees below freezing. It was bitter cold. Your toes are numb the entire day, and then Johnny’s out there operating with bare hands.

In the sand, one of the big problems was that the roost would just destroy drone props. Those props are made of carbon fiber, and when carbon fiber gets compromised, it explodes. It doesn’t crack or bend it, it breaks, kind of like glass would. One day we crashed six or seven times, and there was no way that drone was going to survive. We had to change to a smaller propeller that was more resilient. And then we had to change our flight path around.

Overall, the Red KOMODO cameras did well in the heat, but the batteries had a lot of trouble with it. We also had a Wave camera by Freefly Systems, which was the darling of the shoot as far as what we engineered. We had the very first production models. It’s a super slow-motion camera that shoots at about 400 frames a second. It’s very light and small, only about 700 grams. It allowed us to continuously record and capture all of the dirt, grime, and rocks flying off the wheels in super slow motion.

That presented some challenges, though, because that camera is brand new, and there are always quirks with any type of new technology. Any director or creative would tell you the hardest part is trying to figure out what risk to take and when to be conservative, to make sure that you have the shots. The whole time I was supportive of the risk, but at a certain point, you have to knock this out. We were particularly successful with taking risks on this one.

Were you surprised by what you were able to capture?

What I found on this shoot was the nature of Johnny’s flying is so aggressive and precise, that it opened up new opportunities. Or, either between a mixture of mistakes or the camera not going where we wanted, sometimes it made shots more interesting. We had to say, “Abandon that first idea; this accidental shot is cooler.”

It’s a challenging thing to do in the middle of a shoot. When you can commit to that, and you get to the edit bay, it’s a really rewarding experience. For example, look at the shot where the drone flies through the window. We thought that could be an edit point, and then Johnny actually flew through the window, and it broke what our transition was going to be. We thought, “Well, shit, now where does the camera go?” It was a challenge brought around by a blessing.

Was it worth the risk?

People always ask me, “Is anything faked?” There’s nothing. There’s no creative comp work, nothing embellished. When Johnny flies through the window, he flies through it. We did have the ability to add those things in, but we ultimately decided against it because as soon as we go down that path, it becomes too easy to make everything perfect. Some of my favorite parts are where there’s a little bit of camera wobble or where there’s a bit of camera shake when the car gets close to the drone. Everything in there is a practical shot, and while they’re stitched together through transitions, nothing in there is fake. It’s a testament to Johnny’s abilities as a pilot, and I feel that authenticity comes through.

Sometimes creative boundaries, while annoying, make the best creative product. You do put your head against a wall sometimes, but that’s generally because you’re figuring out something new. If that’s your thought process, whether intentional or not, it brings you to a place that’s hasn’t been explored before.

It’s one of those things where sometimes it feels like a total disaster of epic proportions, and then it works, and it’s perfect. We spent hours and days standing out there with numb toes, or completely dehydrated, thinking, “It’s not working. This won’t work.” You just have to commit to your plan and make it work. Then, when it does, you have this Sparta moment where you throw your hands in the air—everyone knows we got it and then we move on. Those were the best moments in the shoot, just knowing, “Oh, this is going to be great.”

Watch below to learn more about how Porsche’s Drive2Extremes concept came to life.

Drive2Extremes Credits

Client: Porsche

Agency: Keko Dubai

Agency General Manager: Nora Ferneine

Executive Creative Director: Sandy McIntosh

Art director: Rolf Eggers

Agency Producer: Andreea Mititiuc

Production House: Stoked Films

Executive Producer: Charbel Aouad

Executive Producer: Rita El Hachem

Pilot/DOP: Johnny Schaer

Director: Nicholas Schrunk

Precision Driver: Jukka Honkavuori

Producer: Julie Debbas

Servicing company in Finland: Directors Guild Helsinki

Executive Producer Directors Guild: Juha-Matti Nieminen

Post Producer: Anju Purushot

Editor: Emad Hashim, Jake Irish

VFX: Screaming Death Monkey / Jeremy Hunt (No, the rocks exploding into the camera are not VFX/CGI)

Color: Marshall Plante

Music: Another Level by Oh the Larceny – Musicbed

Sound Design: Keith White Audio

UAE drone support: Chopper Shoot

Finland drone support: Kopter Cam