Problems, if anything, are a lesson. Whether we’re defeated by them or come up with a genius solution, afterward they serve as nicely packaged tutorials in what to do and what not to do. So, it only makes sense that the production of a film is a wealth of valuable lessons because they’re filled with obstacles. As famed producer Lain Smith said in a 2014 interview with Screen Daily, “Making a film is a series of problems to solve.”

We talk to a lot of filmmakers on the blog and all of them face problems when they take on a new project. Sometimes they come up with incredible solutions to these problems and that’s what we’re celebrating today. On the surface, they’re fascinating examples of creativity at work. But, we think there’s more to them — maybe they’ll reveal a thought process you could apply to your own problems.

Here are six filmmakers, the problems they faced, and the tricks they used to overcome them:

Lindsay Branham’s Audience Couldn’t Reach Her, So She Reached Them.

We talked with Novo Films’ Founder Lindsay Branham about the potential for VR to play a role in non-profit filmmaking. But, she started our conversation by bringing up another project — one she developed for the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Her problem? The audience she was trying to reach had no access to TVs or theaters. Here’s her explaining a genius solution:

“Our first project was in northern DRC, which is really remote. There are no TVs. There are no movie theaters. So, how do you even show people this stuff? Well, we created this mobile cinema kit that can be transported on the back of a motorbike. It has an inflatable screen and a little projector, both powered by a little generator. You can take this movie anywhere and build these workshops around it as well. So, it’s not just a one-off, watching a movie. It’s crafted very intentionally with activities, games, and discussions, taking the film characters and analyzing them. It’s now rolling out in India. It’s a year-long project built around a 30-minute film that is then broken into scenes and put into a curriculum that ten thousand young girls will go through over the course of a year.”

Our takeaway: Just because it hasn’t been done before doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. In fact, it may be quite the opposite.

Jim Cummings Needed to Share His Vision, So He Made a Podcast.

Thunder Road Director Jim Cummings is getting a reputation for doing things his own way. He tends to ignore the established methods for making a film, so when he was faced with the problem of sharing the vision for his passion project to a cast and crew he’d never worked with before, he decided to cut the miscommunication problem off before started:

“I recorded the whole script as a podcast. When you write a script, it’s your own thing. It’s precious. So, I recorded it as a podcast and then sent it out to everybody and who was working on the film. I would perform all of the characters and I would put in sound design and have music and stuff like that so that the crew is on the same page. Before any cast or crew showed up on set, they were able to listen to the movie. They were able to hear it four or five times before coming to the set. So everybody was on the same page. Because I knew it was working in audio format, I knew that it was going to work in a film.”

Our takeaway: It may not sound easy, but sometimes the only way to solve a problem is to go above and beyond — chances are, it’ll be worth it.

Tucker Bliss Didn’t Like the Prompt, So He Shot His Own Version.

We interviewed Tucker Bliss about getting a film education on someone else’s dime and a big part of that involved working in the commercial world. In this specific case, he was given a project he felt would be best served in a longer form. So, when he got the direction to shoot a short, 15-second spot, he opted to go his own route and it’s safe to say it paid off:

“I definitely try to inject as much of myself as possible. A lot of times it comes down to arguing with agencies or arguing with a client about what stays and what goes — you don’t often win those battles. Hopefully, you get lucky and they say, “You can get a few extra shots.” I did this for a job recently, where the creative director was really cool about the experience. He said, “I know we’re just doing these 15-second spots, but if you want to shoot stuff in between, just go for it. I won’t say anything and we’ll turn off the monitors.” We ended up shooting enough for a 60-second spot. I cut it together and sent it back to the agency, and they ended up selling it to the client. Sometimes the client doesn’t know what they want until you give it to them. They know what they don’t want [laughs] but that helps too.”

Our takeaway: You didn’t hear it from us, but sometimes it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission.

Robbie Samuels Couldn’t Get On-Set, So He Built a Digital One.

Creative people often don’t even see a problem as a problem. It’s more of an opportunity. So, when Hip-Hop Cafe Director Robbie Samuels was faced with a limited timeframe on-set, he had two friends come to mind. It just so happens they’re obsessed with building VR environments:

“We made the whole film in two nights, but on the second night we only had four hours, so, all in, I think we made the film in 13 hours. Which is really, not very much time to make a film [laughs]. We knew we weren’t going to have much time in the diner where we were shooting the piece because it has normal restaurant hours. Luckily, I have two friends that are quite into VR and AR. That’s an understatement. They live for it. I approached them and told them, “I’m trying to pull this off but I don’t have nearly enough time,” and they basically came to the diner, scanned every corner of the location we were filming and built it out in a computer program. It was a lifesaver; it made it possible for me to just put on a VR headset and be in the location, so to speak, so I could plan out all the shot and sequences.”

Our takeaway: A problem, perceived in a certain way, is just an opportunity to make you and your processes better.

Chris Caldwell and Zeek Earl Wrote a Book to Prove Their Concept.

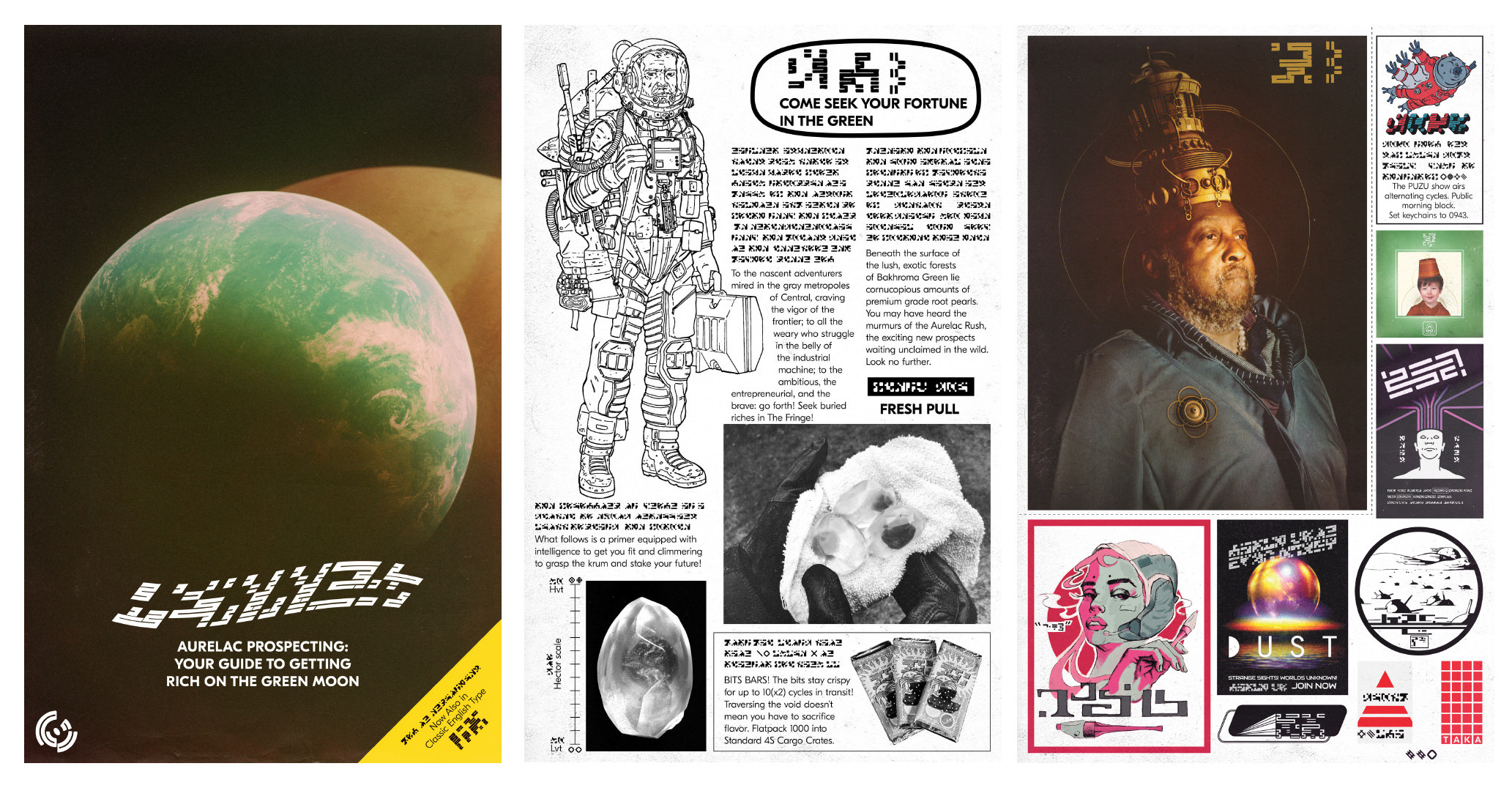

Being young and inexperienced is a problem all of us have faced at one point. When Chris Caldwell and Zeek Earl were pushing to get Prospect funded, they were facing an uphill battle to get support. So, to prove they were committed to their idea, they decided to use the art-director side of their brain to create one hell of a proof-of-concept:

“The biggest hurdle is being a first-time filmmaker because it’s like, you don’t have the job experience to get the job you’re asking for. In our case, we just had to go over the top providing not just the short film but an entire book of concept art. Not just some rough production numbers but a fully fleshed out budget with a ton of resources to back it up. It was a big part of our pitch package from the beginning.

There was so much specificity in the world that we wanted to render. You can only do so much with words on the page in terms of selling other people on that vision. This big book of concept art and design was inspired by Jodorowsky’s Dune. They put together that big book and it became the only remaining artifact from that version of that film. Looking at that book, we kind of wanted to make our own mini version of that. It was a lot of supporting the script with a lot of really specific visual renderings of the world. That eventually made a company comfortable enough to pull the trigger.”

Our takeaway: There aren’t many problems some elbow grease and creativity can’t solve. The trick is to use them together.

Creatives are more equipped than anyone else to solve problems, especially those that have never been encountered before. But, a common thread running between all of these filmmakers is this: initiative. They didn’t wait for their knight in shining armor to save the day. They put on their big filmmaker pants and got to work. So, the real question is, next time a problem comes between you and your film — what will you do?