As hard as we try to create affecting films and images, the truth is, the most important work is often done by amateurs, and it’s often done on accident. As writer David Shields says in Reality Hunger, “What, in the last half century, has been more influential than Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm film of the Kennedy assassination?” Similarly, what professional photographs have you seen recently that moved you as much as the pictures in your parents’ photo album?

In direct contradiction to Ansel Adams’ famous quote about great images being made not taken, the most disarming photography being done today is being done by people who’ve never heard the term “f-stop.”

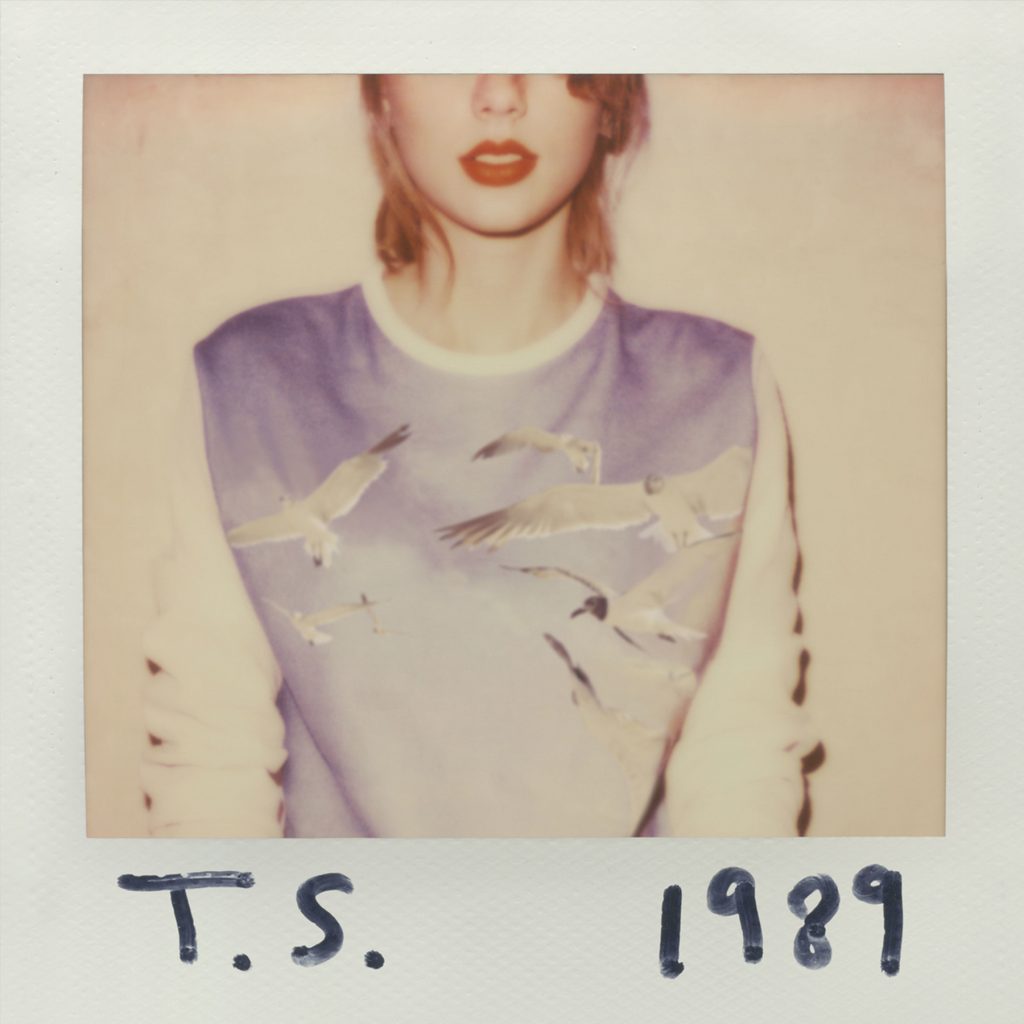

So where does that leave us? We have no idea. But we recently talked about all of this with the brilliant and talented photography duo, Sarah Barlow and Stephen Schofield. The conversation was interesting. This is something that’s been on their minds. Which makes sense since, despite being skilled professionals, their most recognizable work is the Polaroid shot from the cover of Taylor Swift’s most recent album, 1989 — a Polaroid that purposefully mimics something you might find in an old photo album, on a friend’s bulletin board, or even on Instagram. A photograph taken by a friend. Here are Sarah and Stephen.

A big thing I’m constantly learning is the emotion of photography. The biggest thing is the connection you have with the person.

Musicbed: Are you guys in Nashville?

Sarah Barlow: No, we just relocated to L.A. It made more sense to live out here since we were flying out all the time. We’re in the middle of transitioning all of our business out here.

Do you guys have enough water?

Stephen Schofield: We’re drinking a lot of coffee lately. Coffee and wine. Everyone juices out here, and I do too — but it’s wine. I feel like water is a common ingredient of the two.

SB: Wine juice. We’re on the European juice diet. [laughs]

SS: Where are you guys? Texas. Fort Worth.

SS: No way! I did two years at TCU. It’s my dark past. [laughs]

You didn’t like TCU?

SS: I loved TCU, but it was a time in my life when I’d veered off course because of family obligations and things people wanted me to do. I come from a real “traditional work” family with my parents being doctors and my relatives being lawyers. My mom and dad are very musical and creative, but I felt this pressure to do something traditional and keep art as a hobby. I went to TCU for finance. I wore French cuff shirts and pleated pants. It was a dark, dark time. I lost my identity in a Thomas Pink store.

Did rebelling against that time drive you into art?

SS: I’ve always done art, so I didn’t rebel too hard. It was more just realizing this wasn’t for me. It’s not the part of my brain and heart I operate from. My parents were actually super supportive and understanding. Over the years and accomplishments, they definitely see the value and are fully supportive.

How did you guys end up working together?

SS: Long story short, we both ended up in Nashville. I transferred from TCU to Belmont University because finishing school was a nonnegotiable. So I was at Belmont, and Sarah had just moved here from Chicago. Basically we ended up at the same residential building in this urban development section in Nashville. Due to the building being relatively new and occupancy still low, everybody saw each other frequently. A mutual friend introduced me to Sarah, and then we kept seeing each other around the property, which naturally grew into a friendship. She lived in this baller penthouse overlooking the popular pool. I lived on a different level with the pariahs and the outcasts. My balcony overlooked a figurative mudhole — a secluded pool — and Sarah’s overlooked Swan Lake. [laughs]

I was curious about what Sarah did, and I ended up learning more about her art and her wedding photography. When I saw it, I was like, “Man, there’s something very special here.” I told her, “You should probably do something in fashion or music — something beyond what you’re doing now.” And she was like, “I don’t know how to get into that.”

I had some friends from different agencies in New York, so we put together a test shoot. The process turned out to be really fun, and at the end Sarah was like, “Hey, you’re good at what you do. I don’t know what it is, but you should be doing this.” I felt like Rick Rubin. I was like, “Yeah, sure, I don’t know what I’m supposed to do, but I definitely see a path to steer this creative effort!” In some weird way, a collaboration was taking shape.

SB: I told him if he could find time and room outside of music, he should do art direction in New York. And he said, “Well, I think this collaboration we have going on is pretty cool. Do you want to keep doing this?” After a while it just took off. People started noticing what we were doing. I think they saw both of our personalities in it. Mine is more documentary, editorial, real life. Stephen has this fashion, dark-edge type of thing.

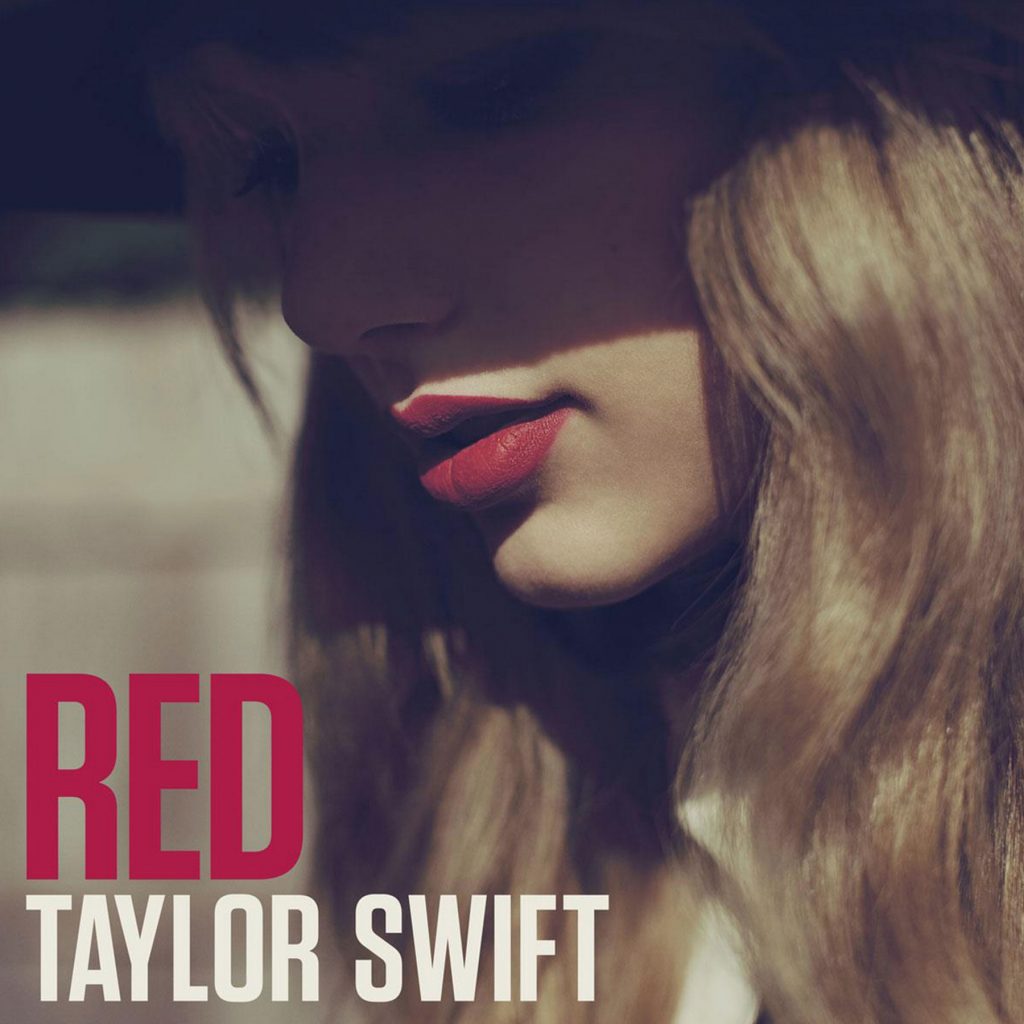

SS: Our first official paid shoot together was Taylor Swift’s Red album.

You have to invest in people during a shoot, give out so they can let their guard down and fully interact and feel like their real selves.

How did you land that?

SB: Taylor is a mutual friend of ours. Stephen and his brother were friends with her years before, and I became friends with her separately. What ended up happening was one of her background singers needed headshots. When Taylor saw them a few months later, she came to me and was like, “Liz showed me the shots you took of her, and I need my album to look exactly like that.” Clearly, this was a no-brainer. I said, “OK!” Before then, I’d been kind of burned out on music photography. A lot of the shoots were super controlling. I needed a new perspective on the field itself and wanted future shoots to be very free-flowing — just the artist and a minimum crew. Luckily for Stephen and me, that’s exactly how Taylor presented the Red album shoot. So it was just the three of us shooting everything together. She wanted everybody else to remain off set, allowing for a more personal and intimate experience.

You guys ended up doing the shoot for 1989 too, right?

SB: Yup. It was like a Polaroid and digital mix. I think we ended up shooting — how many, Stephen? — 460 Polaroids? Something like that?

SS: Yeah, something like that.

SB: Insane amount of Polaroids.

What’s the newest thing you guys have learned about photography?

SB: A big thing I’m constantly learning is the emotion of photography. The biggest thing is the connection you have with the person. You have to invest in people during a shoot, give out so they can let their guard down and fully interact and feel like their real selves.

SS: You have to show confidence. You have to put out good vibes and positive energy to create an environment that allows the subject to be completely disarmed, which allows you to get what no one else has been able to get. That’s the thing we’ve both learned and continue to learn. It’s about the energies you bring to a shoot. You can get real nerdy about all this techy stuff; but at the end of the day, someone who is able to connect relationship-wise with a subject is going to get a better shot. Beyond that, I’m always looking up stuff on Lynda.com about, like, how to use CS2 better.

SB: CS2?! What are you talking about? That was like 15 years ago!

SS: I guess that was a little flashback to the past. I was introduced to Lynda back in college, so I automatically went to CS2.

SB: That’s our dark secret. We still work in CS2. [laughs]

I think there’s something cool about creating an artificial, suspended reality where things look weird and cool.

Are you the type of photographer who takes a billion frames and then edits later, or takes just a few frames?

SB: I’m working on that. I think it depends on what you’re shooting. If you’re in the studio and the person isn’t moving around, then you can shoot slower. I’m a feeler-shooter though, so I move around a lot. We’re all interacting, so there is a lot of action and emotion going on. With that, you do have to shoot more. It’s an area I’m constantly working on though, because I’m trying to get in the zone of thinking I’m shooting on film, even when I’m shooting digital. With digital, it’s easy to shoot a ton. If I’m not careful, I can get into a spray-and-pray type of vibe. Ha.

And you feel like that’s bad?

SB: I think so. Just in terms of time on the back end, it takes a lot longer to edit. So for Stephen’s sanity, it’s better to shoot fewer images.

Does the world look better in real life or in photographs?

SS: Photographs.

SB: Real life! Oh, for sure.

SS: Photographs.

SB: Obviously, I’m totally into photography, but I wish photographs could capture the world as I see it, you know? There are so many times when I’m like, Ah, this would make such an amazing photograph, but a photograph is not going to be able to capture it exactly. A photograph can’t capture how you feel about something, the way it smells, you know?

SS: I don’t know. I think photos can distort reality, and it’s kind of…it’s like a book. You’re able to escape the day-to-day mundanity of reality. I think there’s something cool about creating an artificial, suspended reality where things look weird and cool. That’s what works about movies and books and magazines. Like Steven Klein, his photos are super shimmery and the landscapes are almost otherworldly. You don’t know where they are and that immediately puts you in this whole new environment. I like that. I like the idea of creating your own world. I’ve always enjoyed dress up, so that might be a factor. [laughs]

SB: Basically, Stephen is trying to escape this world.

Do you guys have a favorite photograph?

SB: My grandma recently died, and she had a bunch of photos of herself from when she was younger. She was one of my favorite people ever. And in some of these photos, she’s so cool and independent. There’s such a classic Polaroid look to the photos. They’re perfectly timeless. We strive to shoot like that today.

SS: There’s a photo I keep coming back to that’s so amazing. There are a lot of different emotions in it. It was shot by Steven Meisel, and it’s with Tony Ward and Linda Evangelista. I think it was 1991 for Dolce & Gabbana. It’s somewhat violent but still retains its elegance, and it’s beautiful too. I remember when I first saw it, I was like, Whoa. It made me feel kind of weird, and I think that’s what I like about it. My reaction was something other than, Oh, pretty photo.

Let’s say there could be a best photo ever taken. Is it on a professional photographer’s hard drive or is it buried in a family photo album somewhere?

SB: I think it’s in somebody’s family photo album. There is something so real and authentic there. It’s where people let their guard down — the subject, but also the photographer. The person taking the picture is as comfortable as the person getting her picture taken. When I can feel that in a photo, it’s the best photo ever.

SS: I don’t know. So many powerful images captured by professional photographers and photojournalists have impacted our culture. Like The Falling Man taken on 9/11. Richard Drew captured that. Or what was that other one? The Kiss of Life by Rocco Morabito. Two utility workers were working on a power line, and one of them got electrocuted. The other one gave him mouth-to-mouth and saved his life. That was a super powerful image. The photographer was nearby and able to capture the moment. So it definitely helps if you know what you’re doing with a camera.

Thanks to Sarah and Stephen for taking the time to chat with us. It’s definitely got us thinking. Take some time this week to look through some old photo albums. See what those photographs do to you and how they might affect your work.