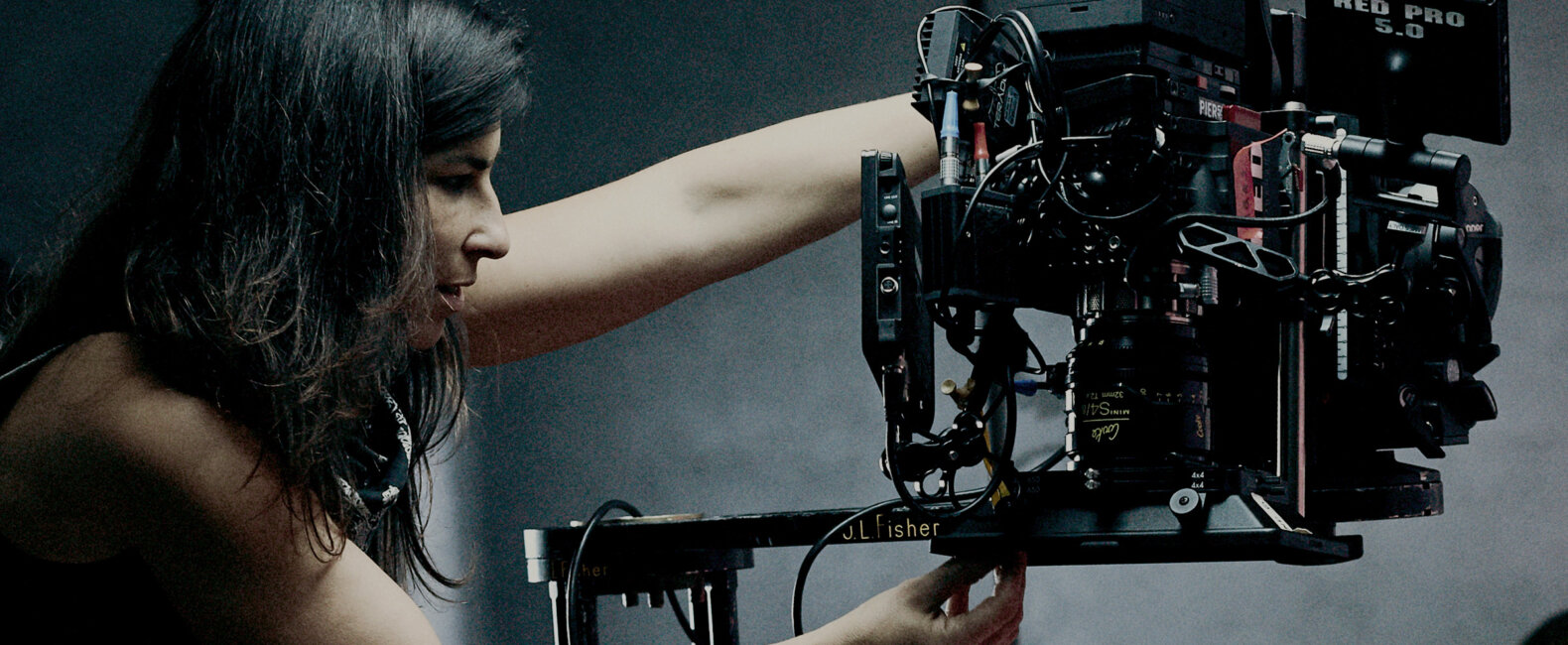

In a film, “Every object, every color, every detail tells a story,” cinematographer Laura Merians told us. “For me, philosophy and filmmaking have a lot of similarities. You’re trying to communicate something. You’re trying to explore a subject or find meaning. As a filmmaker, I’m constantly trying to find the deeper meaning.”

Now, Laura is knee-deep in her next big challenge: bringing her philosophically minded approach to cinematography to her first feature film, Pacified, set in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. “Needless to say, it’s a challenging film,” Laura says. “It’s not a big budget. It’s in an environment that’s kind of dangerous. And it’s in Portuguese, which I speak very little.”

We recently talked with Laura about her approach to cinematography, her background in philosophy, and what she’s learned while making the transition into feature-length films.

Musicbed: You got your degree in philosophy?

I did. I think Steve Martin said, “If you study… philosophy you remember just enough to screw you up for the rest of your life.” [Laughs] Which is kind of extreme. But it absolutely informs everything in my life. I think it allows me to consider things on a deeper level sometimes. Maybe to a fault. The truth is, I thought I was going to be a philosophy professor. It was something I wanted to dedicate my life to. But then I kind of fell into the film world.

Does your experience with philosophy affect your film work?

I think so. I’m delving into a narrative world now and starting to think about the way things hold meaning. I think a lot about the symbolic communication of light. I believe, in many ways, that light is as important as dialogue. They are both integral parts of the story. They both have meaning. Every object, every color, every detail — it all tells a story. For me, philosophy and filmmaking have a lot of similarities. You’re trying to communicate something. You’re trying to explore a subject or find meaning. As a filmmaker, I’m constantly trying to find the deeper meaning, or at least approach things from the infinite possibility of perception. I think a lot about how we perceive things — real things or fake things — and how that plays with people psychologically.

What do you mean by real or fake?

Perception is a slippery slope. It is, by definition, subjective. What people see in the world might not be real. That, to me, is what’s exciting about the medium of film. How can you play with the way the audience sees the world? Film allows you to direct perception. There’s tremendous power in that. And a lot of fun.

It now makes perfect sense that you produced a film called Solipsist.

Oh my god, yeah. Solipsist is the perfect representation of my philosophical background. Andy and I are good friends and love exploring the visual metaphors of philosophical theories. I became a producer because I really wanted that movie to be made so I probably got deeper into it than most other cinematographers might have.

Do you think all films are solipsistic?

There are definitely philosophical arguments to support that idea. Heidegger talked about the metaphysical world that’s revealed by the artist. He suggested there’s no actual meaning behind it; it’s just the world that’s been created by the artist. It’s something you experience. Every project has the potential to have deeper meaning. But when it comes to light theory and color theory, you have to consider how the perception of certain things affects people on a cognitive level. And they might not be conscious of its impact — even as they’re experiencing it.

Is there a linguistics of light?

I definitely think so. What you choose to highlight, what you choose to leave in darkness — that’s the language of lighting. And there are so many different types of light: gentle light, dreamlike light, misty light, hot light, dark light, central light, or subdued light. There are so many types of light and so many ways to describe it.

Do you worry about overthinking things, making things too metaphorical?

Sometimes. but I don’t think it’s a bad thing. I think it’s a necessary part of the process just like technical planning. You have to stay open to inspiration and I’m always trying to find the magic. And the way you tap into that is by being totally present when you’re working. You can plan ahead and “overthink,” but you also need to be ready to strip all of that away, when necessary. There is a time to overthink and a time to be decisive.

Do you follow any set principles when it comes to lighting?

For me, it’s all about creating a mood, which is a balance of being captivating but not distracting. I lean toward minimalism and simplicity and figuring out what would make sense in an environment. Every time I walk into a space, I think: What does this really feel like, and why is it lit this way? What are the motivating sources?

You’re working on your first feature now. What differences have you noticed between short and long form in terms of cinematography?

With long form, it’s all about the story. It’s about letting the visuals serve that story. You have to train yourself not to impose artificial or distracting ideas on the work, but still allow for whatever feels right for the performances, for the characters. In the commercial or music video world, you’re allowed to do whatever you want, in any kind of order you want. You have confidence and immediate approval when the client’s happy. The client’s happy, the commercial is over, and it’s done. A feature is a lot more vulnerable. The stakes are a lot higher. It’s pretty terrifying because it’s not just the cinematography; the acting, the direction, and the story will also be judged.

It must be frustrating that so much of the process is out of your hands.

I wouldn’t say frustrating. I’d just say it’s more of a leap of faith. You hope everything will have synergy, that you’ll create something great. It makes you respect and value a successful movie and how hard that is to achieve. Everybody’s intentions are good, everybody is trying to do their best work, but some things are more successful than others. For me, it’s about focusing on my job as the director of photography, and letting other people do their jobs. You have to have faith that everybody is going to collaborate. That’s what I love about filmmaking: you get to collaborate with so many talented people. And if you’re lucky, you create something amazing.

How do you sustain your energy and focus over a longer timeline?

That’ll be one of the biggest challenges. On commercial or music video projects, you’re typically on the job for around a week. The odds are stacked in your favor. For a movie, it’s like, wow, after a week we’ve only just started. With this latest feature, the director and I literally spent an entire week sitting in a tree house in the middle of nowhere, breaking down the script. It took a long time. It all takes a long time. But that’s what it takes to be successful. You have to be ready for that.

Have you learned any lessons recently that have changed how you work?

I was recently working on a movie as a camera operator with an amazing DP. I watched how he worked with complicated camera moves, the way he set his A and B points. Making a clear plan with the director and following it up with blocking. It probably sounds very basic, but that was kind of a game changer for me. He took the time to be clear about how everything was going to happen. I learned the value of slowing down, thinking, communicating what you’re thinking. So much of good cinematography is about good communication, being clear about what everybody wants and talking it through so that everyone understands. I was coming from the commercial world where the pace is much faster because you’ve very limited time. But when you’re dealing with narrative film, you have to think about how to pace the story – this is not a 30 second or 1 minute piece – which means that slowing down and really evaluating your next step makes all the difference in the world.