How far are you willing to go for your films? Are you willing to break the law? Get arrested? Spend 18 hours hiding from helicopters to get a single shot of a dam exploding? For Ben Knight, one of the filmmakers behind the recent (and excellent) documentary DamNation, the answer is yes.

“Pretty much everything we did in the film was illegal,” Ben told us. “Every single day we were trespassing.”

But Ben is no stranger to working around the system. After dropping out of high school during his senior year, Ben carved out a career for himself as a photojournalist before finally transitioning into documentary filmmaking. He’s living proof there is no “right way” to get into this type of work. Ben’s lack of concern for the “rules” has become an asset. The monomania that made him a bad student has turned him into a visionary filmmaker.

We recently talked with Ben about his career, his activism, and how far he was willing to go to make a film about dams.

Here’s Ben.

Did your 18 years in Telluride influence your desire to make films?

Absolutely. But not because of the Telluride Film Festival. It was actually because of something called Mountainfilm Festival. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it, but it’s a documentary film festival that happens every year in May. It’s pretty incredible. I was a slide projector bitch for the festival back in the day, and I was consistently blown away by the energy a film could build in a room. It was impossible to ignore. You could tell people left that theater really thinking about what they had just seen.

Were there any specific films you saw at Mountainfilm that inspired you?

Yeah, actually. There was one that no one’s probably ever seen called The Black (1999). It was about these guys BASE jumping into Black Canyon National Park, which isn’t far from Telluride. It was shot on 16mm, and it was the first time I’d seen BASE jumping on film. I’m dating myself, but back then you couldn’t just pull up videos on the Internet. I remember being so affected by that short film. It was really well shot and really simple. Mostly natural sound, I think. The simplicity made it feel approachable. Like, hey, we could do something like that.

At the time, I was working as a photographer at the daily newspaper, and I’d started to wonder if film was a more effective medium. I wanted to try it at least. So my friend and partner Travis Rummel and I started transitioning out of still photography and into video.

What was it like being a photographer for a paper? Did you learn anything that has stuck with you?

Yeah. Working at the newspaper was basically my college. It was the best experience. I owe so much to it. I learned to write, which is really important. And being forced every single day to go out and find something interesting in a pretty news-less town was not an easy task. But I had so much pride that I wouldn’t let myself put a crappy photo on the cover. I would force myself to shoot the occasional photo essay and then beg the paper for space to put it in. I think being able to tell a story in one image is the absolute best training for filmmaking.

I was working in a photo lab. I was the guy developing people’s vacation pictures at two in the morning.

How do you find stories in a pretty sleepy town?

I had a police scanner. So there were always car accidents and avalanches. A lot of avalanches. In the summer there’d be forest fires, and I would drive hours to cover fires. At the same time, though, there were the high school girls’ volleyball games to cover. The town softball league. I couldn’t be too picky.

I kind of glossed over it, but you dropped out of high school? That’s pretty huge.

I’m one of those people who really struggles to learn something that I’m not interested in. Any class I didn’t have some interest in, I couldn’t engage with it. I just didn’t care. The classes I was slightly interested in — photography, for example, woodworking, or tech theater — I just crushed them. If I was interested or inspired, I did really well; but that wasn’t enough. By the time I was a senior, I didn’t have enough credits to graduate, so I bailed. I knew I wanted to be a photographer, and I didn’t have the money for college anyway.

How did you get the job at the newspaper?

I was working in a photo lab. I was the guy developing people’s vacation pictures at two in the morning. Anyway, the photographer from the local paper would bring me his film every day, and I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. So one day I strategically laid out on the counter a couple of photos I’d taken. When he came in, he was like, “Oh damn, can I run one of these in the paper?” And I was like, “Are you shitting me? Of course you can!” Later, he decided he wanted to take a week off for Christmas, and he asked if I would cover for him. I jumped at the chance. That was the beginning. I don’t think I ever had a résumé.

So you started working for the paper and then eventually transitioned into filmmaking.

Yeah, Travis borrowed some money to buy a Panasonic DVX. At the time we were obsessed with fly-fishing, and we’d go to the Black Canyon to fish. You have to hike down over 2,000 vertical feet to go fishing there. We started dragging that camera with us and filming ourselves playing around, learning to film. My friend had an iMac with iMovie, and I’d go to his house to edit. We eventually showed the film to people, and everyone was like, “Damn, guys, there’s actually something there.” Without even trying, we’d accidentally made something kind of interesting. That film ended up being called The Hatch. Our first film.

Once we got a taste of making a film that made a difference — that made people feel something and think differently about something —it feels like an addiction. It’s what we thrive on.

If nothing else, that film gave us confidence. It got into Mountainfilm, which blew our minds. And then it went on to get into the 2005 Banff Mountain Film Festival in Canada. We were speechless. I didn’t think it could get any bigger than that.

Did you know then that you were going to be a filmmaker?

I knew I was on a new path, but neither one of us quit our day jobs right away. I kept working at the newspaper to make ends meet. It took a while for both of us to commit to starting our business. We ended up making another fly-fishing film and then our first feature documentary, Red Gold, which was really defining for us. It was about a proposed open-pit mine in Bristol Bay, Alaska. We spent the whole summer filming, and in the end I think the film was pretty influential in the fight against the mine.

Is activism a big part of your motivation for making films?

Well, once we got a taste of making a film that made a difference — that made people feel something and think differently about something — I don’t know…it feels like an addiction. It’s what we thrive on.

What are some of the difficulties of making a film like that? A film about an issue?

Well, you have to be able to pull at people’s heartstrings. Even people who have cold, dead hearts. You have to captivate them somehow. So even with a subject like dams, you have to find a way of humanizing that story. We spend so much time trying to find characters with a little bit of spark, something you can connect with. For DamNation we shot over 50 interviews and used only 13 of them I think. It’s really hard to find those special characters. I think a lot of people think that just because they interview someone, they owe it to them to be in the film. But it can’t work that way.

So let’s talk about your latest film, DamNation. How did this story come to you?

Yvon Chouinard, founder of the Patagonia clothing company, had always wanted to make a film about dams. He and his friend Matt Stoecker decided that Travis and I might be the right people to make it. So they approached us, and we were like…well, first of all, we were honored. But then we said no. “No way, this is too hard, too broad, how could we ever keep people in their seats for an hour and a half with a film about concrete walls?” It seemed impossible. So out of pure fear of the subject, we said no.

We went in blind. We knew nothing about the issue. We knew nothing about dams. It was this amazing learning experience, finding these little stories and these characters.

About a week later, Matt Stoecker called us back and said, “Are you guys sure?” And we were like, “Actually, no. We’ll do it.” We had no work at the time, and this was like a dream come true for a filmmaker, to have a company call and say, “Will you make a film? We’ll pay for the whole thing.” We were so lucky. I think our filmmaker friends hated us because we were so lucky. But actually, I wouldn’t call it luck because it turned out to be the hardest three years of our lives.

What changed your mind?

There was one major thing that turned us around: two of the biggest dam removals in history were about to happen. So we were like, “Okay, at least we’ll have those visuals. At least there will be something dynamic going on.” Not only could we film these dams coming down, but if we waited long enough, we could maybe see the ecosystem rebounding. So we loaded all of our shit into a van and drove all over the country, figuring out the rest of the story as we went. We went in blind. We knew nothing about the issue. We knew nothing about dams. It was this amazing learning experience, finding these little stories and these characters.

So you just drove around?

Pretty much.

How did you know where to go?

Our first stop was Montana. We interviewed this amazing writer named David James Duncan. He basically melted our faces; he was so poetic and articulate. He talked about rivers in a way we’d never heard anyone talk about them before. He also gave us some ideas of places to go, things to see, possible story ideas. It was pivotal. We ended up with a rough trajectory, but along the way we randomly discovered the coolest stuff.

At one point I was flipping through a magazine and saw a story about this guy who used to paint cracks on dams. He was an Earth First! activist. He would rappel off the tops of dams and paint them. I was like, “Are you kidding me? We have to find this guy immediately.” That’s the kind of stuff that makes a film about dams watchable.

I don’t get off on danger, but it was absolutely necessary if we were going to make a film that was engaging and fun.

You ended up finding more people who paint dams, right?

The lawyers hate it when I talk about this, but I think it’s a beautiful story. We found Mikal, the guy who used to paint the cracks. After we interviewed him, we were so inspired. We decided to go paint 160-foot dotted line with a pair of scissors on the face of an old dam in California. I asked some friends if they’d be down to help, and before I could even finish asking, they were like, “We’re in.” It was probably the best night of my life. I’ll never forget it. We leaked photos of the scissors, but no one believed it for almost two weeks. They thought it was Photoshopped. Once they realized it was real, it got a lot of press. So…yeah. It may or may not have been our idea.

Was filming dangerous?

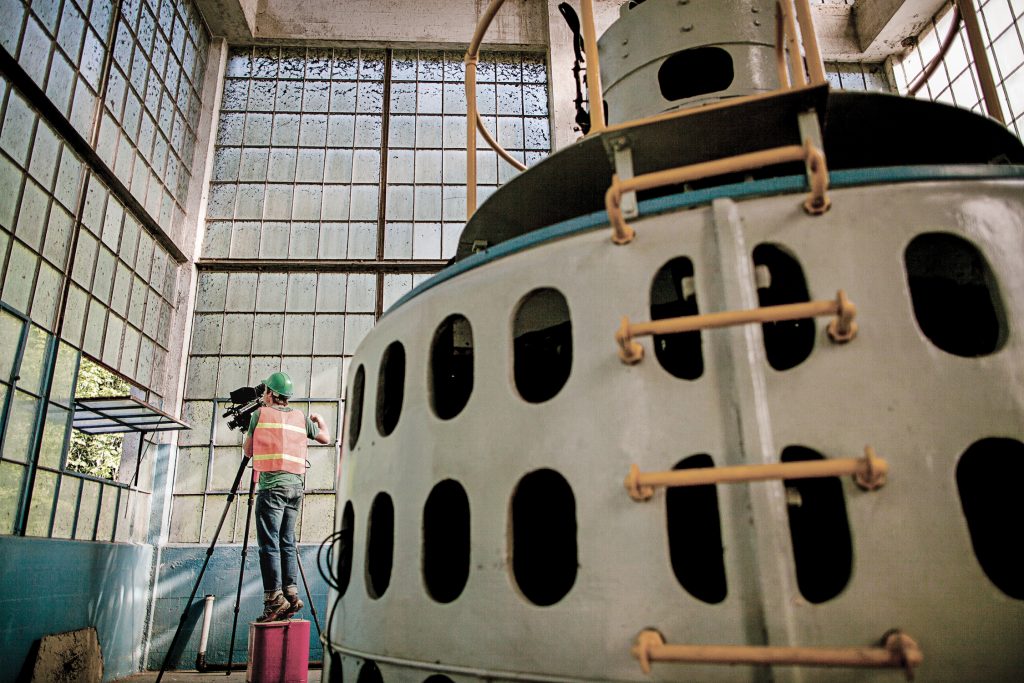

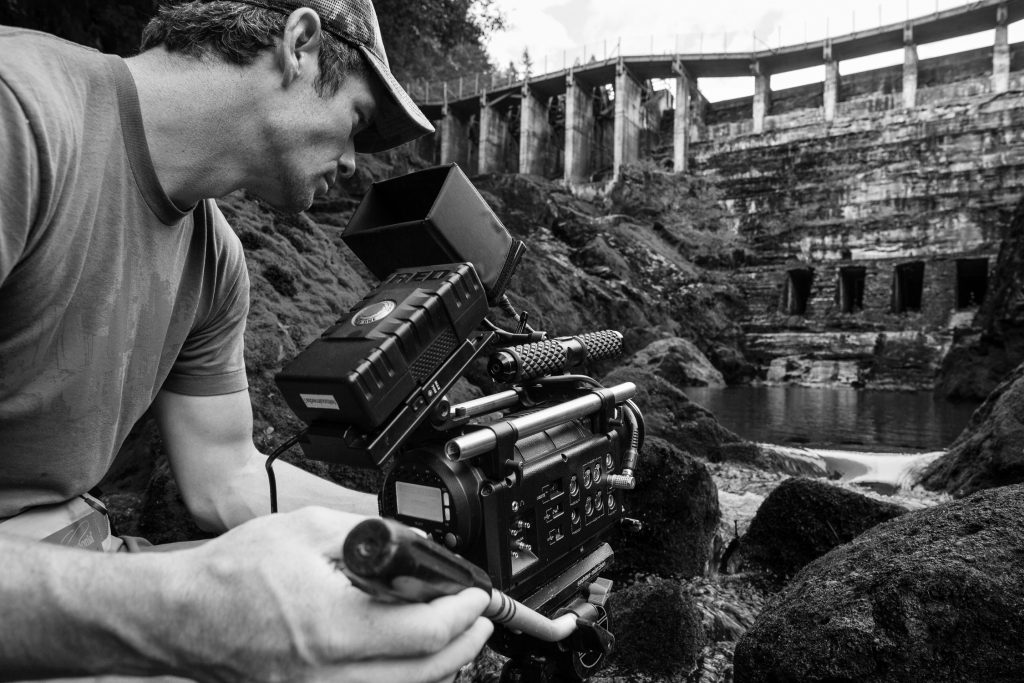

Pretty much everything we did in the film was illegal. Every single day we were trespassing. At one point, I had to sneak into a dam blast zone in the middle of the night wearing full camouflage. We built a camera blind for me to hide in for 18 hours because they were going to blow up the dam the next day. The demolition crew wouldn’t let us anywhere near it. They had a helicopter out looking for people, so I had to lie there under this camouflage blanket. The shot came out pretty cool though.

Another time, we tried to kayak through this lock system on the Snake River and ended up getting in this huge confrontation with security. The local sheriffs came out and threatened to arrest us, accused us of being terrorists. It was a terrible idea but we needed a way to add some visual context to the issue.

Do you enjoy working on the fringe like that? Sneaking around the red tape? It seems like it might turn a lot of people away.

Well, part of it was that I had so much respect for Patagonia as a company. Their boldness and their message and what they do. I wanted to show them that we were willing to get outside of our comfort zones too. I wouldn’t say I crave doing illegal things, but I definitely have an issue with authority. I get really frustrated with people who won’t let us film. It drives me insane. I don’t get off on danger, but it was absolutely necessary if we were going to make a film that was engaging and fun.

Are you happy with how the film came together?

I’m really proud of it. I’m proud that people can actually sit there for an hour and a half and not get bored out of their minds. I’m so sensitive to how an audience is reacting to a film. It goes back to those moments at the Mountainfilm Festival when I was a kid. I’m very sensitive to pacing. But I don’t mean to sound like I know what I’m doing, because I don’t. We still have so much to learn. But, yeah, I’m proud.

When you dropped out of high school, did you see yourself ending up where you are now?

No way. I felt like I was going to be a failure. It was a pretty depressing time. Despite knowing what I wanted to do at the time, I wasn’t confident by any means. The truth is, I didn’t think any of it was going to work out. I was scared out of my mind and horribly embarrassed. It was a low time, for sure.

It’s funny, though, because since then I’ve taught photography in a high school. (They let someone with a GED teach high school photography.) And I’ve seen a lot of kids who are brilliant but don’t do well in the normal school system. It’s not meant for everyone. I have to be careful not to encourage them to drop out.

It’s easy to trick yourself into thinking there is a right way and a wrong way of doing things. It’s easy to go with the flow. But after talking with Ben, we’re pretty sure that going with the flow will never result in anything interesting happening — and certainly nothing interesting happening on film. You have to push yourself outside of your comfort zone. You have to break a few rules. You have to trust yourself and your vision, and be willing to follow where it takes you.