One week after graduating from high school, Cale Glendening drove his mom’s car 1,465 miles from Oklahoma to Los Angeles to begin his career as a filmmaker. He didn’t have a plan, a job, or even a place to stay. He’d taken one video production class (and got a C in it), and he would soon be rejected by USC’s film school. But as you’ll see from our conversation below, discouragement has a sort of reverse effect on Cale. It makes him work harder.

An internship, a chance meeting with Janusz Kamiński, and a $30K loan later, Cale was now 23 years old, standing in a video store, and looking at his name on the cover of a feature-length documentary. “When I saw it in the store, I almost cried,” he told us. His work and his risk-taking had paid off. And it continues to pay off still.

His latest film (the second in a series called On the Road) recently got a Vimeo Staff Pick and features the music of our very own Salomon Ligthelm. Check out the video and then read Cale’s story below. It’s wild.

Describe your path to becoming a filmmaker.

Okay, let’s rewind. I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma. Muskogee, Oklahoma. Merle Haggard’s song “Okie from Muskogee” — that’s our claim to fame. That song made it into the movie Platoon, which won Best Picture [in 1987], the year after I was born.

I grew up playing sports because sports are what you do in the Midwest, especially in a small town. When I got to high school, that’s all I wanted to do. My dad was a standout college athlete and was invited to try out for the Cincinnati Reds, but he messed up his knee. He had two championship rings from a D1 college, and that’s what I wanted too. Even in high school I was already revolving my future career around baseball. I was just this big jock who got along with everyone, but I was also a cocky little shit.

I ended up getting in a big argument with one of my teachers and requested to switch classes. There were only two other classes available, and one of them was Video Production. So I picked that one. After one week in that class, my entire life changed. That summer, my dad and I drove to New York to visit film schools.

Did you feel good at filmmaking right away?

Absolutely not. I was just enjoying the ride and the creative process. I remember the first time I figured out what a dolly shot was. My friends were pushing me around on this cart, and I was like, “Wait. Let me pull out the camera.” Something clicked and I realized, Oh, this is how they do that. Each time I figured out something new, it was the best day of my life. At the end of my senior year, I ended up making a C in Video Production.

You made a C?

One of the worst grades I ever got was in the only class I loved. The thing was, Video Production wasn’t a class for filmmakers. It was for kids who wanted to work at news stations. The teacher had us making slide shows. No one else in the class was motivated, so it would take them two weeks to make a slide show. I’d make my mine in five minutes and then be like, “Okay, now I want to go out and film.” I never followed the curriculum ever. To my school’s absolute credit, though, they could see how serious I was about pursuing film, and they let me take 30 days off of school for a film internship, which turned out to be pretty pivotal in my life.

So you ended up going to film school?

Well, I quickly realized these film schools were more interested in academic merit than creativity or potential. I’d never really challenged myself in school, never did a day of homework in my life. I was truly discouraged when I realized that most of these elite film schools wanted kids who’d been in AP classes since their freshman year and scored 30s on their ACTs. I was like, “Being a genius doesn’t make someone creative.” But in sports, coaches pound into you that you need to get better every day. That’s what was written on the wall of our locker room: How did you get better today? I’ve taken that motivation and adopted it into my process of filmmaking. So I was discouraged, but I wasn’t going to let these schools keep me from doing what I loved. I decided I was going to L.A. anyway. I packed up my mom’s car and drove from Oklahoma to Los Angeles. I was 18 years old, one week out of high school, and I threw myself into the mix.

You just drove to the city?

Yes.

Did you have some sort of plan?

No.

What were those first days in L.A. like?

Ramen and Easy Mac. But it was magic, man. This was the big leagues. I felt pure excitement. I found a roommate, and we found an apartment, and for the first four months I slept on the floor. I didn’t own a single piece of furniture. My roommate was this girl who was a singer/actress, which I thought was so cool…before I learned that everyone is a singer/actress. I was so oblivious to the world. But God bless her, she’s one of the reasons I got the wheels turning out there. She was scouring Craigslist for jobs as an extra, and she knew how bad I needed work. So she sent in a picture of me too. They responded, but they only wanted me.

So I showed up on set, just trying to be Mr. Friendly, and I ended up becoming friends with one of the PAs. I told him I wanted to PA or intern or something, and he was like, “Okay, at the end of the day, you just follow me.” He ended up getting me a job as a PA, which led to more jobs as a PA, and then eventually an internship.

You didn’t mind doing mundane work even though you had such a creative drive?

I was just a sponge. I was the dude with a pen and paper writing down terms. I didn’t even know what a DP was. I just wanted to educate myself. The woman who hired me as a PA was happy with my work ethic, and she hooked me up with an internship with a music video production company. My first job was four straight days of recataloguing their entire vault, packing everything into boxes, and moving it out so they could put in new carpet. Then recataloguing and putting the vault back together. We’re talking about a thousand tapes. It was gnarly. But after that, I was on good terms with everybody; and I started working on jobs for 50 Cent, The Black Eyed Peas, Pharrell, Snoop Dogg. All these big artists.

These were legit sets. Quarter of a million dollar budgets. 35mm. I got to intern under directors like Francis Lawrence who’s now doing The Hunger Games. Marc Webb who went on to do The Amazing Spider-Man and (500) Days of Summer. These guys were on the cusp of their prime, and I got to study how they worked. I remember one day when one of the agents saw me scribbling in a book. He came over and grabbed the book out of my hand and was like, “What the hell are you doing?” He thought I was doing something wrong. He looked at my book, though, and he’s like, “Are you taking notes?” And I was like, “Yes?” And he’s like, “Why?” And I said, “Because this is what I want to do. This is my classroom.” He smiled and handed the book back to me. It was this weird moment.

Later in my internship, I ended up on really good terms with the production manager. One day she pulled me aside and told me I had seniority and could pick any job I wanted. I was pumped because we had jobs coming in almost every day. I was never interested in the musician, just the director or the DP. So one day I walked in and the production manager had this smile on her face. She goes, “You might want to check the list today.” So I checked the list and I was like, “Is this a joke?” And she’s like, “Nope. We confirmed it this morning.” They were doing a video project for Madonna, for her Confessions Tour, and Janusz Kamiński was shooting it. Spielberg’s DP. She held up her end of the deal and said, “It’s yours.”

So we ended up shooting these horses in the mountains of Southern California, and it was absolutely gorgeous. What I immediately liked about Kamiński was how much he enjoyed what he did. How much fun he had shooting and creating. At one point he was like, “I’m not getting the shot I want. I want to be lower. We need to dig a hole.” And we’re like, “What?” And he’s like, “Dig me a hole.” So of course we dug him a hole, and he’s like, “All right, now I want to get in the hole and shoot the horses running over me.” We were like, “What?!” We talked to the horse wrangler, and he said the horses would probably see the hole and run around it. The wrangler goes, “Of course, I can’t account for all of them.” So everyone is freaking out, telling Kamiński to just put the camera on a stand, to just rig it. But he’s like, “No, I’m getting in the hole and that’s that.”

Here’s a guy who could honestly say this shoot was peanuts compared to what he was used to doing. He’d shot Saving Private Ryan, for Chrissake. But he was still willing to risk his life to get a shot he knew was going to be great. That moved me. I thought it was incredible. So he gets in this hole by himself, they let the horses loose, and they run full speed in this perfect stream around him. And the shot was gorgeous. It was absolutely gorgeous.

If you want to be a filmmaker, you have to go make films

At the end of the day, they were shuttling people back to the production hub, and there weren’t any seats left on the shuttle. So Kamiński was like, “I want to walk anyway.” So he started walking back by himself. And I was just like, Oh man, this is my chance. Go talk to him! This was right around the time Munich came out, which is one of my favorite things he’s done, and I had the LA Weekly with me that had Munich on the cover. So I ran after him and asked if I could walk with him. He was like, “Of course.” Super nice guy. I was like, “Hey, I don’t want to be that guy, but could you sign this for me?” I held up my copy of LA Weekly. And he was like, “Really?” I think it took him by surprise. And I was like, “Well, yeah. I’m a huge fan of your work. You’re one of my favorites. You’re a huge inspiration for me.”

So we ended up walking together, and I was asking him stuff like, “In War of the Worlds,how did you do that 360 shot around the van?” All this technical shit, and I could tell he was actually enjoying it. We talked for 15, 20 minutes, and when we got near the production hub, I was like, “Do you mind giving me advice on one more question?” And he’s like, “Sure.” I said, “I’ve been out here for several months, and I’m starting to realize how hard it will be to become a director.” I told him I was debating continuing on my current path or going to film school. I told him I didn’t know which option was best. And he said, “Well, what do you want to do?” And I said, “I want to make films.” And he looked at me point blank and said, “Well then go make films.”

I sat there for a second like, “That’s it?” And then it hit me. If I wanted to do something, I just had to start doing it now. The simplicity of it was so profound. I’d made my career into some crazy equation, when really it was the most elementary of ideas. You need to make the projects you want to make. If you want to be a filmmaker, you have to go make films. I remember him saying, “Get your friends, go make films, do whatever it takes.” I’ve taken that advice with me everywhere since then. I have that LA Weekly he signed framed on my wall. A month later, I quit my internship and went home.

Did you start making films?

No. After Janusz gave me that advice, I found out my grandmother, who is like my mother, had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. I moved back home to be near her. I wanted as many moments with her as I could get before she didn’t remember me. I’d started taking pictures as a way of continuing my craft, but that first year I was very lazy. I wanted to be doing more, but I didn’t have the resources. I was discouraged. I felt like, “Well, what the hell can I do from here? I can’t make films. I don’t have gear. I don’t have money.” My grandma noticed this, and one day she looked at me and said in broken English, “Don’t hate me for this…” She handed me a three-page note. It was unfinished. Alzheimer’s had started taking her speech, but she could still write. Her note was basically three pages of her telling me how much she loves me, but how disappointed she is in me that I am wasting my talent and potential by being lazy and not doing the things I’m capable of. That letter hit me so hard, I didn’t know what to do. I just cried. I mean it fucking hurt. But I knew it was tough love. She was challenging me. That’s when I decided to step up my game. I started shooting photos every single day, started learning everything I could, started finally taking everything Janusz had told me to heart. I applied to USC’s film school.

Did you get in?

I’m looking across the room at my rejection letter right now. I have it framed on my wall, right next to the LA Weekly Janusz signed for me.

Why did you frame that?

It’s a motivator. An inspiration. When I didn’t get into USC, it fueled my fire. I went to my mom and dad and told them I was ready to go all in on this, to start making films. We went to the bank and took out a major loan. I had zero collateral, so my mom put up our house.

Whoa.

My parents’ support was unbelievable. We got the loan on my 22nd birthday, and two months later I shot my first music video. While I was cutting that music video, we had this crazy snowstorm, and I was super excited because I’d just gotten my Redrock Micro 35mm converter. My friend and I went out in my front yard and shot footage of snow falling. Falling in reverse. Playing with depth. Still just as excited as I was in high school about every new thing I could learn.

I released the music video and the snow video, which was literally called Snow Test, and a few months later a guy named Ryan Clark contacted me. Ryan is the founder of a band called Demon Hunter and the owner of Invisible Creature, which I think is one of the best design shops out there. Anyway, Ryan hits me up and he’s like, “We saw your music video and your snow video, and we want you to shoot a feature-length documentary of our upcoming tour. We’re not approaching anyone else. This is yours if you want it.”

Out of nowhere?

Out of the blue. He literally offered me the job based on those two videos. But the catch was the band could afford only me. There wasn’t room on the bus for anyone else. So not only did I produce the entire thing myself, but I also wrote it, directed it, DP’d it, did all the audio, all the editing, all the coloring. I did the DVD authoring. The photography. I literally did every single job.

Did you feel in over your head while making a feature-length documentary?

I didn’t feel in over my head until I got home and it took two weeks just to transcode the footage. It was all P2 media. Once all the footage was done transcoding, I just sat there for a solid 30 minutes in sheer panic. Then for the next month, I did nothing but play video games. I refused to edit. Refused to even look at my computer because I had no idea what I was going to do. Finally, it got to zero hour when I had to start if I was going to make the deadline. They’d given me a solid three months to edit, and I only had two months left. So for two months I spent no less than 10 hours a day, seven days a week editing the film until it was done.

The night I sent them the rough cut, I didn’t sleep at all because I was so nervous for their feedback. The next morning, Ryan Clark called. It almost sounded like he was crying. He was just like, “You brought me to tears last night. My wife was crying. We don’t have a single change. Not one revision.” Of course, two days later they had a revision, but they liked the documentary so much they made it part of the main packaging and put my name on the cover of the album (45 Days). It was the first time something said A film by Cale Glendening.

I want to be a filmmaker and that requires me to make films. This is what I have to do

How did that feel?

I didn’t know he was going to do that. So when I saw it in the store, I almost cried. An hour and a half documentary that I’d made was in stores nationwide with my name on the cover. And my mind just went back to what Janusz had said while we were walking off set that day: “If you want to be a filmmaker, then go make films.”

How old were you at that point?

I was 23. All of that happened the year after I took out the loan (which I paid back before the year was up, by the way), and it’s all kind of steamrolled since. I’m still a freelancer. It hasn’t all been magical, of course. I’ve had those situations where it’s between me and another person to work on a dream job, and I’ve lost out. Heartbreaking stuff. But I always go back to, “You know what? This job requires me to create, so that’s what I’m going to do. I want to be a filmmaker and that requires me to make films. This is what I have to do.”

About a year after the documentary came out, I moved back to L.A. for the second time. I pulled up in a beige ’97 Chevy Venture that I’d bought with the leftover money from the loan. I’d meant to buy a nicer car, but I spent too much on gear. You want a humbling experience? Imagine being invited to Fashion Week and pulling up in a beige ’97 Chevy Venture.

That’s how you know you’ve made it.

Look, Mom! I made it!

Is your grandma proud of you?

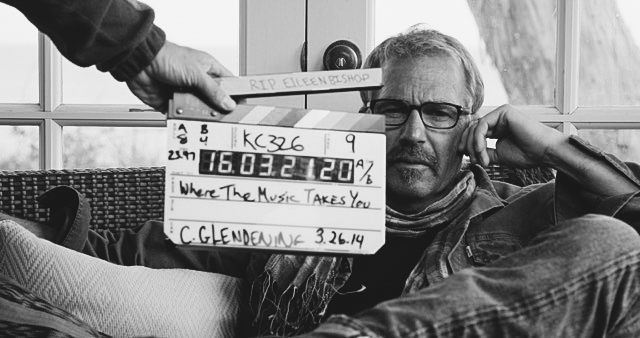

My grandma died last year, and I didn’t make it home in time to say good-bye. It crushed me. The day of her funeral, I got an email green-lighting me on a job I developed for Kevin Costner — the biggest job of my career. I don’t think that’s purely coincidence. I put her name on the slate: RIP Eileen Bishop.

It’s so easy to overcomplicate things. Like Cale said, to think there is some equation that adds up to a successful career. But really, filmmaking is as simple as getting your friends together, thinking up stories, and hitting Record. Forget going the long way around. Forget “career paths.” Go straight at what you want. Make the projects you want to make. Start right now.