Dana Shaw is a hands-on type of guy. A film editor, stained-glass artist, and self-proclaimed bird charmer, Dana’s preferred method of editing documentaries is to lay out all his notes and stills on a large piece of butcher paper, so he can physically move the pieces around. “I’m really tactile,” Dana told us. “So being able to put those themes into categories and print out related quotes and put them on this ‘paper edit’ helps me organize my thoughts.”

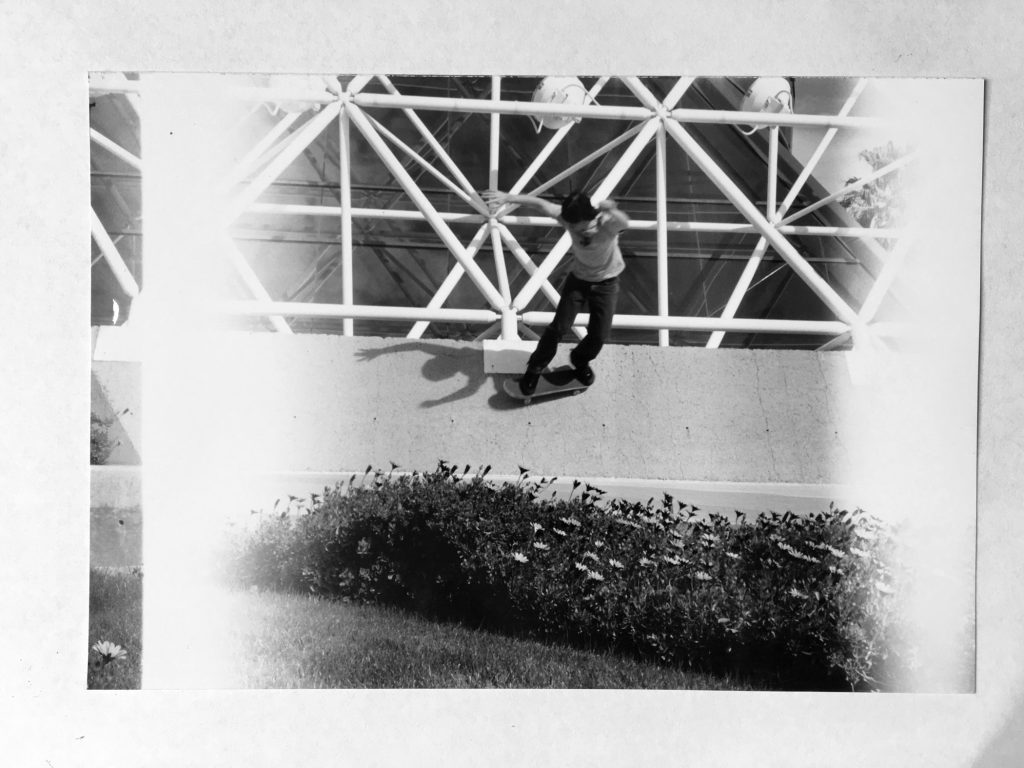

It’s not your traditional approach to editing. But then Dana isn’t a traditional guy. After getting his start in film producing skate videos (and getting tips from his neighbor, the legendary skate film producer Jon Holland), Dana spent the next seven years of his life traveling the world with a camera and a skateboard. And when he finally enrolled in the film program at The Art Institute of California – San Francisco, he focused all of his energy on creating world-class documentaries.

We talked with Dana about his career, skateboarding, and his untraditional approach to creating and editing documentaries.

Musicbed: How did you become a filmmaker?

Dana Shaw: It all started with skateboarding. I grew up in Encinitas, California, which was like a mecca for progressive skateboarding in the mid ’90s and early 2000s. I remember seeing people with video cameras in the hallways of my high school. They were always shooting skateboarders. I was a decent skateboarder, but not nearly as good as my friends. So I’d end up holding the camera a lot more than they did. It’s the typical skateboarder/cinematographer story.

What I had that most kids like that didn’t have, however, was Jon Holland — one of the most influential filmmakers in skateboarding. He lived nearby. So as a 9th or 10th grader, I was able to ask him a lot of questions about how to shoot. And we had guys like Chany Jeanguenin, Kyle Leeper, Richard Angelides, and Danny Way shooting at our YMCA. I got to watch all of these professionals come to our neighborhood to make videos, while I was taking classes in video production at my high school. The teachers would try to get us to shoot scripted projects, but I’d be like, “How about we just shoot a skateboard video?”

From the minute I got out of high school until I was 25, I made my living shooting skateboarding. It was great but also kind of disconnected from reality. I was traveling a lot. I’d shoot in Barcelona twice a year, maybe more. And in other places. I was never anyplace long enough to have a regular life, you know, like with a girlfriend. Things adults have.

What is it about skateboarding that lends itself to film? You don’t really hear about filmmakers getting their start shooting football or baseball games.

That’s a good question. When I was growing up, only two or three skateboard videos came out each year, and they were the only way to verify that someone had actually completed a trick. It was about establishing cred to the skater. So as much as it showed off skateboard maneuvers and stuff, it was mostly about marketing. As a kid, you’d see these incredible moves, and you’d hear this rad music, and you’d be like, “Oh my God, they’re my hero!” Skate videos introduced you to a style and aesthetic. The way people move, the way they push. You feel it like you’re there. It’s a sport that can be really visual. Like surfing. You can capture the rhythm and the flow and the movement. And the skateboarder is a part of that. They’re planning what their moves will look like and how they’ll feel, because it’s about them. That means being involved in both the shooting and the editing. I don’t think filmmakers who shoot other sports videos can do that so easily.

How did you make the transition to editing and documentaries?

I was watching a lot of films and documentaries at the time, which inspired me to take things to the next level. I started applying to film schools and got accepted to The Art Institute of California in San Francisco. I went there with no money in my pocket, but I was immediately exposed to all of these oddball filmmakers. People like Rick Prelinger who was really into archiving and digging out these ephemeral films — stuff we just don’t think about as film, like home movies from the ’50s or ’60s, lost landscapes of San Francisco, stuff found in dumpsters. It was inspiring. The head of the Film Department at my school was Lexi Leban, who made the documentary Girl Trouble. She really cared about the scene and wanted to support me as an artist. I’d gone to a ton of different film schools and showed them my skateboard reel, but no one cared. Lexi was like, “Wow, I really see that you care about this stuff. What you’re doing is interesting.” It was there that I learned how to become a documentary filmmaker.

What does your documentary process look like? Did your skateboard video experience carry over?

Well, back then I was shooting a lot and I wasn’t editing a ton. I knew how to edit, but it was just a part of my background tech skills. I didn’t have a theory or a workflow. But I did have good intuition about people, and I knew how to gain intimacy with them. I’ve always been a people person, which helps. But I didn’t know how to structure a conversation. It was just like, “Hey, let’s talk.” My angle was, “Okay, you’re a skateboarder. What are your influences? What are you drawn to? What inspires you? Who inspires you?” Learning how to keep things interesting was mostly done by trial and error. I did a lot of really long interviews that led to nowhere.

Did your subject of interest still orbit around the skating world?

No, it totally shifted. I put skating in the backseat and opened my focus to social and political topics, especially how they connect to music — punk rock music — and the history of San Francisco. I became really interested in the people and music connected to sociopolitical activism. The first thing that caught my attention was Weather Underground, Bernardine Dohrn, and the whole history of activists in the ’60s. Shit like that got me really sparked.

Do you think it’s better for a documentarian to investigate a subject or place they’re extremely familiar with, or tackle a subject that’s outside their expertise and look at things as an outsider?

That’s a really tough question. I’d say it’s a bit of both. For instance, I didn’t start noticing things about my friends and where I came from until after I’d left. All the crazy histories and good stories weren’t apparent to me until I’d had some time away from it. Until I longed for it. But there’s also something to be said for discovering something new. Britton Caillouette is a director I’ve worked with a ton. He taught me how to be curious about new places and topics. When he rolls into town, he talks to people and smells things and hears things; it leads him toward the story. He trusts his gut. To me, that’s the romance of observational doc filmmaking. Being informed with your own personal journey in these places is what drives the story and angle. So even if you’re working commercially, even if you’re working on something brand oriented, it’s the unknown that makes things interesting.

What do you look for in a subject?

I look for a subject that has history and intention. That’s huge. Where you come from is what makes you who you are. It’s nice to have conflict, struggle, or adversity, because that’s how you become defined as a person. And in that conflict, how a person makes decisions — that’s what’s interesting to me. Here’s the secret: you know there’s a good story when the hair on the back of your neck stands up. It’s like a predator-prey experience. You just feel it.

What’s your process as a documentary editor?

First, I lay out everything in one long sequence and listen to the whole thing, start to finish. Then I’ll watch it all without taking notes. Afterward, I’ll let it sit for a while, kind of digest it. That’s the point when I start in on my creative notes, figuring out the themes. What kind of arc can I carve out of it? Where’s the struggle, where’s the catalyst, where’s the resolution? I’ll pull out those themes and make a flow chart on a big piece of butcher paper that has meticulous tape lines. I’m really tactile, so being able to put those themes into categories and print out related quotes and put them on this “paper edit” helps me organize my thoughts.

Then I’ll print screen grabs from the footage and start laying those out on a separate line, so it almost turns into a flatbed editor. It’s right in front of me, and I can move things around. I learned this approach from reading Walter Murch. It’s how he cuts films. Doing this tells me what I need from the next shoot. It’s like you go to the market and buy all the ingredients and make your soup; but you have a month to get it right. You taste it, see if it’s any good, put it in the fridge, reheat it, and come back to it — over and over again. Maybe it needs more cumin. Maybe it’s not spicy enough. Or it’s too spicy, so you pull out the spiciness.

Has the way you edit today changed from the time you first started taking editing seriously?

That’s the funny thing. I take it less seriously now. The expectations and the deadlines and the billable hours can all build up in your head. That’s not going to help your creative process. Instead of worrying about what others think I need to do, I pay more attention to the media and the work in front of me. Developing my own process — one that’s outside a computer program — activates me as a visual learner. And that’s where the poetry comes from.

What’s the most valuable lesson you’ve learned so far? Is there an experience that changed the way you think or the way you work?

Trusting yourself is probably the most important thing you can learn. Close the door. When you have the opinions of everyone in the room and you’re trying to be creative, it’s next to impossible to make anything happen. I need time with a project. I need to think about it and have some patience with it. I know that’s impossible sometimes. But after the director has weighed in, I need some alone time with the material, space to trust in myself and my process. That’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned: trust yourself. Don’t get caught up in the “rules” and the technology. Understand what you’ve got and what you can do with it.

When I was in film school, the instructor for my final portfolio class told us: “It’s not how many high grades you get; it’s not how many films you’ve edited; it’s not even what they look like or how good they are that’s important. It’s how you think. How you think is what’s going to make you an original person and a desirable editor. Just keep moving forward and making decisions based on what your body tells you.” I really can’t add much to that.