What’s a more accurate term: passion project or obsession project? If you’re talking about Variable’s latest film, Rocket Wars, then obsession is definitely the right word to use. And not just for the filmmakers, but for the subjects of the film too.

Rocket Wars is a short, cinematic documentary about an absolutely insane tradition that happens every year in the Greek village of Vrontados. Citizens assemble nearby two neighboring churches, and they shoot upwards of 100,000 rockets at each other while people are observing Mass inside the buildings. It’s a mock battle whose origins are both old and mysterious — which is what drew Salomon Ligthelm to Vrontados in the first place.

“I was… intrigued by the backstory,” Salomon told us, “or more so that the backstory kept changing, depending on who you asked. So part of the intrigue was, What’s the truth here? Let’s go find out.”

What Salomon and a small crew from Variable found was a group of people obsessed with rockets. People who spend eight months of the year and almost all of their income preparing for a four-hour conflagration. As far as passion projects go, the people of Vrontados have taken things to another level.

We recently talked with director Salomon Ligthelm and executive producer Tyler Ginter about what we can honestly say is the most beautiful short film we have seen this year, Rocket Wars.

F+M: I read that the idea for Rocket Wars came from a random YouTube clip?

Salomon Ligthelm: Yeah. You know how sometimes late at night you end up falling down the YouTube rabbit hole? Just clicking links and watching whatever is trending? And after you watch the video, up pops a screen with nine more videos to watch? On one of those frames, I saw the rockets. It turned out to be a journalistic piece about this annual tradition in Vrontados, where they shoot 100,000 rockets at each other. I thought, Wow, maybe there’s something we can bring to this story that hasn’t been done yet. So I kept that in the back of my mind for a while. And then a few months after I came to the States, I mentioned it to Tyler.

Tyler Ginter: No. Actually, Salomon, the first time I ever met you in real life — we had been talking on Skype for years — but the first time you flew to New York and we got brunch together, you told me all about the rockets. You showed me screen grabs of rocket wars that morning. I was like, Okay, here we go. We’re going to have to make this happen for Salomon.

What I loved about the film is that you guys found a subject that is so compelling on its own.

SL: When you pull back all the artifice, what I’m really trying to get down to is whether the root thing we’re shooting is interesting. Is what we’re saying actually interesting? Anyone can use art and aesthetic, but what I hope people really care about is whether or not the subject matter is interesting. It frustrates me to see videos that are well edited, well shot, and use cool music, but are they saying anything?

Salomon, I remember you saying that your inspiration for ANOMALY came from a random screen shot. It sounds like the inspiration for Rocket Wars came about similarly. Do you seek out ideas or do they come to you?

SL: The best stuff usually feels quite serendipitous. It’s not the product of my intention. Just this morning someone asked me if Rocket Wars was meant to be a celebratory angle to everything happening in Greece right now. A glimmer of hope. I was like, “No, that was totally not part of the design.” But I feel like when we find things that really resonate with people, it’s usually outside of our construct. It’s something we’ve stumbled upon.

Often the projects you put the most thought and work into don’t hold up as well as the ones that just kind of happen. The ones you just kind of find. I think the best work happens when you’re not in absolute control.

TG: You’re never in absolute control. I think Salomon nailed it. The more you try to control the creative process, the less the artist’s intuition and heart come across on-screen. And not just the artist, but the subject too. Take Rocket Wars, for example. It’s this festival and tradition. It’s this timeless thing. And we wanted to capture what that felt like in the moment. The more you try to control or plan, the more life you squeeze out of it. But that’s also part of the risk: You show up without a perfect plan. But if you spend too much time or too many resources trying to make a perfect plan, you risk losing the innocence.

Often the projects you put the most thought and work into don’t hold up as well as the ones that just kind of happen.

I think you guys are hitting on one of the most frustrating parts of being a creative person. There’s rarely a direct link between working hard on something and it turning out well.

SL: I don’t have it figured out, but it seems like you need to let yourself be the product of the process. Then things tend to happen a bit more organically, rather than trying to strong-arm your way through. Just this morning someone asked me if Rocket Wars turned out how I was expecting [it to]. And the answer is no. The answer is always no. In Rocket Wars specifically, one of the things we wanted to do was give the whole thing this low-contrast kind of look. Make the blacks really milky. We had references, but it wasn’t happening. It just didn’t work. So we ended up with a punchy contrasty look instead. And it just worked. We have to keep reminding ourselves to always be open to change.

TG: If you control something too much, you lose the ability to fail. And failure is a key part of art — a key part of the process. There’s so much pressure on a commercial project or a feature film project, that there’s no room for failure. But on personal work like this, you have that flexibility. And if you can embrace the fact that some things aren’t going to work out — that some things are going to fail — it opens up new opportunities for the art to come through, especially when you’re working with real people in real scenarios.

What drew you guys to this particular story?

SL: When I first watched the clip, it was the fact that they were shooting rockets at each other and this was part of some tradition. And, at the same time, people were inside the church having Mass. I was also intrigued by the backstory – or more-so that the backstory kept changing depending on who you asked. So part of the intrigue was, What’s the truth here? Let’s go find out.

When you get on the ground in Vrontados, you immediately see that these people are OCD about rockets. They truly love it. People eat, sleep, and breathe rockets. Eight months out of the year, aside from their 9-to-5 jobs, they spend all their waking hours building rockets by hand. Everything from the poles to the pouches to the gunpowder, which they make with pine tree wood. We were there during the last week of preparation, and some guys were doing all-nighters to get their rockets ready. They literally spend all of their money on these things.

And they shoot them all off in one day.

SL: In four hours.

TG: There are so many layers and dynamics to this story. As soon as Salomon got excited about the project, that got Khalid Mohtaseb [the director of photography] excited about the project, and that’s what got me excited: seeing these artists find a story they really wanted to tell.

I feel like the guys in the film were kind of doing the same thing you guys were doing. These rockets are like the biggest passion project of all time.

SL: I never noticed that, but yeah. Totally.

TG: It’s so true.

SL: And it’s gone in a moment. That’s the craziest thing. And that’s why you have to enjoy the process. Because the joy of releasing something is so fleeting. It’s like, Oh, great. It’s done. Everybody’s been wondering about it, and now it’s done. But hopefully you’ve actually enjoyed the process, which is something that has to be learned, I think.

TG: I think people are naturally always looking for the next thing. That next end result. It’s hard to take a moment and enjoy the process. That’s why at Variable we try so hard to work with our friends and work with people we enjoy. Because the dangerous part is that — just like those rockets — it can turn into an obsession very quickly. If we’re not taking the time to step back and take a look at the bigger picture, then the end result will never be that fulfilling. The fulfilling part is creating stories and working with your friends.

Can you tell me about your decision to use that St. Augustine epigraph — “We do not seek peace in order to be at war, but we go to war that we may have peace”?

SL: To be honest, a friend of mine sent it to me. I usually get to the point, as a creator, where I lose my objectivity. So I have a couple of people I send my work to who can give me notes. One of those friends sent me the quote, and I thought it was interesting. It leads the film with a thought, which helps; because otherwise, you don’t really know what these guys are talking about. It feels like we’re preparing something, but you don’t know what until the beginning of the second act when we introduce the rockets.

…as a creator…I lose my objectivity. So I have a couple of people I send my work to who can give me notes.

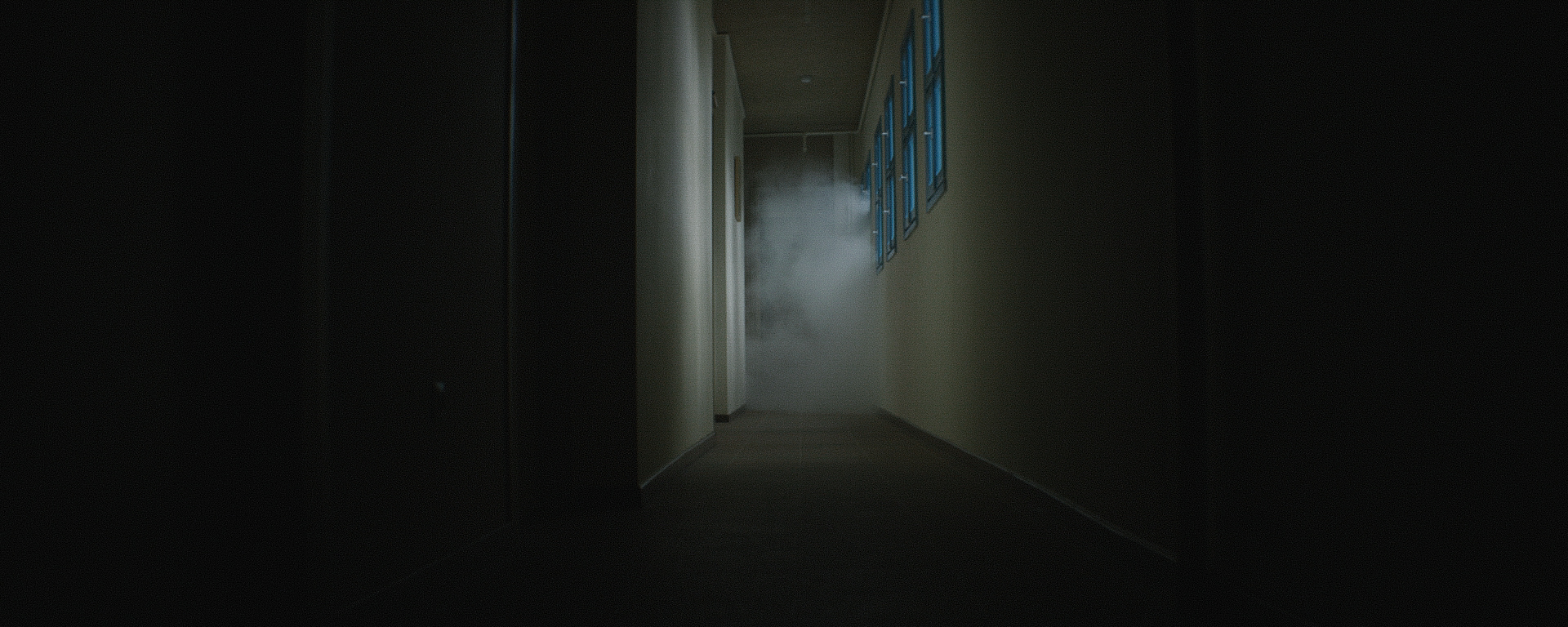

That smoke in the hallway is epic.

SL: That shot was quite a fight. It required a smoke machine, which required a generator. Plus, getting a smoke machine to Greece was like the most difficult thing you can imagine. And the generator weighed a ton. We had to have four people carrying it. And it was all for this one shot, and I wasn’t even sure what the shot was for. I was insistent on it for vibe and mood, but I didn’t really know how it was going to be used. We hadn’t even interviewed the people yet. So when I started editing, I was glad it felt like there was a nice moment to use it. It elevates the film into a cerebral dimension — where you know it’s not real, but it feels spooky and introduces a new chapter without being literal.

How much of the film was constructed like that?

SL: That was really the only shot like that. Aside from that, we just reacted to the environment.

TG: Our goal was for the film to feel like a documentary, but have this narrative, cinematic approach. Obviously the rocket wars section is as real as it gets. They’re shooting these rockets for four hours, and our guys strategically divided and conquered in three different units. Salomon and Khalid were shooting on the RED, Jon Bregel was running around with the Phantom Flex, and then we had SnapRoll Media flying from a rooftop to get aerial footage. Everyone was communicating on walkie-talkies. That scene was the biggest risk of all. We could have gotten the best stories and interviews; but if we didn’t nail the rocket wars section, it would have fallen flat.

When you left, did you feel like you’d gotten it?

SL: We were moving so quickly that Khalid and I didn’t even have time to watch dailies. We had no idea what we were shooting, apart from what we could see on the monitor. It was like, I think we got it? I didn’t even listen back to the audio to make sure it was good. It was all just so reactive.

Were there any specific lessons you guys learned on this project?

SL: Hmmmm.

TG: Hopefully we learned something.

SL: I think what I learned through this experience is how fascinating real people and real experiences are. How much potency there is for the audience when they understand that what they’re watching is real. We could have done the rocket wars with CG and VFX, but it’s so much more powerful when you know it’s real.

We could have done the rocket wars with CG and VFX, but it’s so much more powerful when you know it’s real.

And the same goes for people’s stories. Some people’s stories are so outrageous. Like the man in the film. He’s this flower shop owner who is also this hard-ass ringleader/rocket maker. Exploring the real side of humanity is very interesting to me at the moment. A lot of first-time filmmakers get hung up on the aesthetics — and I was hung up on them too. But you can often miss what we were talking about earlier: What’s interesting about this at a root level? And it comes down to interesting people, interesting events, interesting stories.

TG: For me, Rocket Wars was a reminder about how important it is to do personal work. This type of story is why we all got into this craft in the first place. We want to make work that’s pure. Work that comes from who we are and what we believe in. This project was kind of a nice refresh for our whole team.

If you weren’t working on a passion project before, hopefully you’ll start one now. Fascination can lead to incredible things, whether it’s a 200-year-old rocketry tradition, or a five-minute film about it. Trust your interests. Let your passion inch toward obsession. Light things on fire. What you make doesn’t have to be good; it just has to be you.