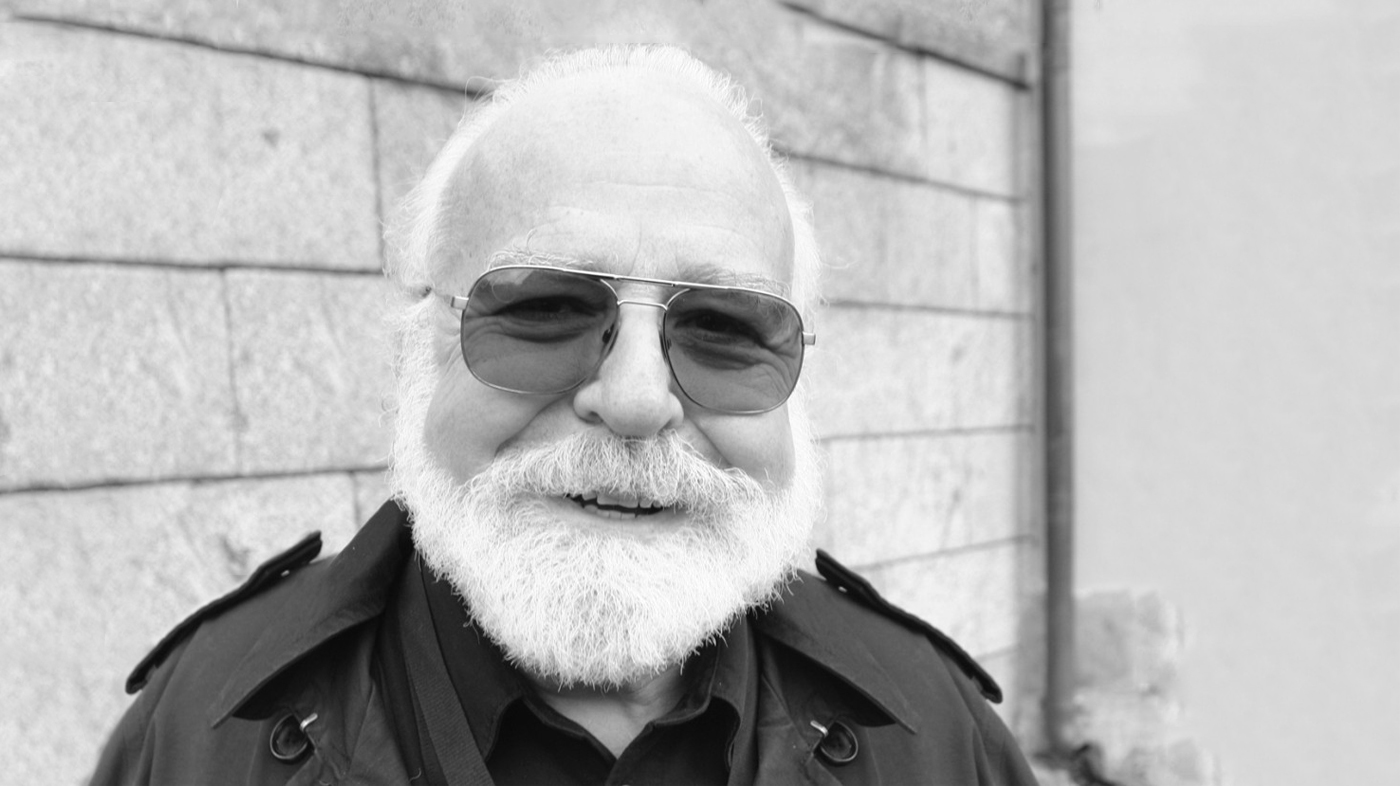

What makes a short film a short film? If you asked us a month ago, we might have told you that a short film’s defining characteristic is, well, its shortness. But not anymore. For the past few weeks, we’ve been trading emails with Dr. Richard Raskin, a professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, and one of the most brilliant and active short-film theorists in the world. Not only does Dr. Raskin make short films, teach short films, and speak around the world at conferences about short films, but he also edits an academic journal about short films called, appropriately, Short Film Studies.

After spending so much time with the form, Dr. Raskin realized a short film isn’t merely a condensed version of a feature, but rather a different narrative form altogether. A form that doesn’t require dialogue, character arcs, or even conflict — the very things we thought storytelling was all about.

We asked Dr. Raskin to explain his theories and models to us in a bit more detail, and what he told us has changed the way we see films. Hopefully it will do the same for you.

Here’s Dr. Richard Raskin.

Musicbed: Would you mind describing your surroundings? Where are you at the moment?

I’m in an apartment in the very centre of Aarhus, overlooking a canal and sidewalk cafés. The apartment is bright even on a rainy day like this one. No sounds right now except for my tapping on the keyboard.

Why the short film? Why have you devoted so much time and energy into understanding this form?

When I began teaching hands-on courses in film production in the mid 1980s, it was clear the only formats my students could manage to produce within a one-semester course were short films of one kind or another. And before long, I realised fiction was what they wanted to work with the most, and so did I. But most books on screenwriting deal with feature-film storytelling, and the only books focused on the short film at that time were uninspiring and not very useful. So I had to develop my own narrative model that could pin down what was specific to short-film storytelling, without being formulaic or restrictive of the students’ creativity, and help catch beginner mistakes. It took a number of years and a lot of trial and error to develop a viable model. But one finally took shape, and it seems to be working quite well.

Very few academics are passionately interested in the short film. Sometimes I get the impression that I am the only one. In any event it’s a niche I am happy with, and I get to give seminars on short-film storytelling at festivals and film schools.

A whole other way of answering your question would be to say I love narratives that are very short and meaningful. Jerry Seinfeld once said: “If I wanted a long boring story with no point to it, I’ve got my life”. I have a low boredom threshold; and films running, for example, six or seven minutes are just right for me.

Can you tell me more about these narrative models you’ve developed?

Before I can say more about the narrative model, I have to prevent a major misunderstanding.

When I talk about the short film, I mean a film that typically runs less than 10 minutes. Often the short film is confused with a much longer form, running about 25 to 40 minutes, which is the preferred format for graduation films at most film schools. There is no proper term in English for that longer form, which in Scandinavia is called a novellefilm. The novellefilm is essentially a miniature feature film, while the short film is an art form in its own right and with a much freer form of storytelling.

There are three major differences between the short film and longer cinematic narratives. First of all, in the short film there may or may not be conflict between characters. This can be hard to accept for people who have read a lot about screenwriting, since it is stated categorically in virtually every screenwriting book that conflict is the heart of all drama and there can be no storytelling without conflict. But some of the best short films are entirely free of conflict, while others are to some degree conflict driven.

Second, while the main character in a longer narrative is expected to undergo a fundamental transformation of some kind — called a character arc — in the short film, the main character generally remains the same throughout. And instead of a character arc, what you find in the short film are character moments — moments when characters make decisive choices that change their situation.

And the third major difference is that in the short film, wordless storytelling is a real option.

These differences are so fundamental that the narrative models designed for feature films are simply not at all applicable to short-film storytelling. Those standard narrative models are generally sequential in the sense that they prescribe a set of phases the story is presumed to go through as it unfolds, and they invariably presume the storytelling in play is conflict driven. They are also terribly formulaic. For example, stating there must be a specific type of plot point on page 25 of a 90-page script! I would avoid that kind of approach because the short film is too free-form for a formulaic straitjacket of that kind, and, as already mentioned, because the short film may or may not be conflict driven.

Instead of a sequential model, the narrative model I use is based on the view that when short-film storytelling is at its best, it can be understood in terms of opposites that balance one another in a dynamic interplay. Do you want to hear about this, or shall we move on to other issues?

We’d love to hear more. What do you mean by “opposites that balance one another in a dynamic interplay”?

Here, in a very brief version, are the seven pairs of opposites that balance and complete one another in a dynamic interplay:

1. CHARACTER FOCUS ↔ CHARACTER INTERACTION

The best short films generally make it clear from the start whose story they are telling — a quality that might be called “character focus”. Once viewers know whose story it is, they can begin to feel at home within the fiction and have a way of measuring what is most important within the film. At the same time, it is generally character interaction that provides the vitality needed to capture and hold the viewer’s interest in the film. And as already mentioned, that interaction does not have to be conflictual.

2. CAUSALITY ↔ CHOICE

When short-film storytelling is at its best, causality flows from choices characters deliberately make. Main characters who make things happen are more interesting to the viewer than characters to whom things happen. And one of the most common beginner mistakes is to design a main character who is too passive. Another common beginner mistake is to use mere temporal succession (“and then… and then…”) as the connective links between events, rather than relationships of cause and effect.

3. CONSISTENCY ↔ SURPRISE

In the short film, one does not have the luxury of introducing or defining characters gradually. And once defined for the viewer, they generally remain consistent with their initial definition. No character arc. At the same time, the viewer should never be able to guess what the characters will do next. The characters’ behaviour should be as unpredictable as it is consistent.

4. SOUND ↔ IMAGE

Short films rarely take full advantage of an opportunity to make the action as interesting to the ear as it is to the eye, by making sound an integral part of the action itself, rather than merely an auditory backdrop for the action. Let characters produce sounds or listen for sounds, so there is a dynamic interplay between sound and image.

5. CHARACTER ↔ OBJECT

Short films sometimes allow physical objects charged with meaning for their characters to bear important parts of the storytelling. In this way, inner experience and outer objects can be connected, and the characters’ touching or even caressing of meaningful objects or portions of the décor can enable the viewer to work out what the characters must be feeling or thinking. Letting characters touch each other is also a good way to connect the outer with the inner.

6. SIMPLICITY ↔ DEPTH

Paradoxically, short films telling simple stories are most likely to be experienced by viewers as being deep, because they leave a habitable space inside for viewers to enter and explore and construct meanings. Films full of clever twists or excessive detail are more likely to be experienced as superficial, keeping the viewer at a distance as an observer rather than a participant.

7. ECONOMY ↔ WHOLENESS

This is the “less is more” principle in short-film storytelling. Killing darlings and cutting to the bone are sheer necessities for giving a short film its breathtaking economy. At the same time, when a short film ends, the viewer should be left feeling that it is complete and even inexhaustible. The effective managing of closural strategies can be essential for achieving this interplay of economy and wholeness, by bringing the story full circle and leaving the viewer with something meaningful to replay in his or her mind as the credits roll. I know this must sound very schematic, but I hope the essentials get through — even though I can’t illustrate each of these storytelling strategies for you with the concrete examples I show when I’m giving a seminar on this subject.

Could you tell me more about these “closural strategies”?

An example I like to use for closural strategies is a brilliant Irish film called Sunday. The film begins with a shot of three books lying horizontally on the floor and supporting a table leg. The book covers are in radiant color. The camera then rises and makes its round of the dinner table, showing each family member. Then a drama plays out, with the father slapping one of his sons for asking a perfectly natural question, and the camera returns to its starting point under the table showing the three books once again. Only now their covers are black and white. This is a classic closural strategy: returning to the point of departure, bringing the story full circle, but with something changed as a marker that something has happened. In this particular case, the change — the disappearance of color — could signify that the father is squeezing the life out of his family. That was the original ending planned in the storyboard.

Then at the end of the shoot, the filmmaker — John Lawlor — thought of having two white horses gracefully walk along the spine of the central book. And those horses, which belong to the world of the child, are a ray of hope in an otherwise dark ending. They also leave the viewer with something meaningful to replay in his or her mind, and to interpret as the credits roll. That’s what I would call planting a symbolic event or act five or ten seconds before the end of the film. Another important closural strategy.

Is it possible for a filmmaker to use these pairs of opposites but create a film that is still unsatisfying for the viewer?

Absolutely. There are no guarantees. And a short film in which only two or three of these seven polarities are working can still be a little masterpiece. These storytelling strategies are not rules, but rather opportunities for enriching the storytelling. And each of them is so potent that two or three of them can do the trick.

Do you find it helpful to begin writing with the closural strategy in mind and then work backwards?

Some people do that and get good results. When choosing the opening shot for a short film, it’s always a good idea to consider how good it might be to return to that shot at the end, so it bookends the film.

Are there common mistakes you see your students making in their approach or execution of their short films?

There certainly are. Maybe the most important one is not focusing enough on bringing the viewer inside the characters’ experience. Instead, they waste precious time on unimportant outer things like moving characters around from one place to another.

Another common mistake is not having enough causality in the story, not setting up chains of interlocking causes and effects. When the causality is missing, all there is between the beats of the story is temporal succession — “and then… and then…” — which is boring.

Many beginners also take for granted that the character they place at the centre of their story will automatically interest the viewer. That just isn’t the case. A central character has to deserve the viewer’s interest, has to earn it and be worthy of his or her special status in the story. And of course, instead of telling their story as economically as possible — cutting to the bone and killing their darlings — many beginners think the longer their short film is, the more it’s like a “real” film. So they pad it out with filler, and the result is a tedious film that seems to go on forever.

Another common mistake is to take for granted that the intended function of a particular shot will be what the viewer actually experiences. Beginners tend to see things through the prism of their intentions, and it can be difficult for them to learn to see with the viewers’ eyes. I could go on for hours, but those are probably the most important and most interesting beginner mistakes.

I’m curious if you have any thoughts on what makes a main character compelling in a short film, especially in light of conflict not being necessary.

Among the main things that count, one is difficult to pin down: getting an actor whose screen presence is likeable. I don’t think anyone will ever be able to explain likeability. Some actors have it, others don’t. Another factor is a storytelling issue and easier to describe: in general, viewers will gladly identify with and care about a character who is in charge of his or her own story, who knows what he or she wants and how to get it.

When you assign a short film in your class, do you set specific parameters? What does the assignment look like?

I begin with a 90-second exercise with these ground rules: (a) one location, (b) one character must nod to another in a way the viewer will understand as meaningful, (c) maximum of one word of dialogue, no voiceover, (d) there must be a POV figure, and (e) an entire story must be told with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

For the main production, a four-to-seven-minute fiction film, the one specific requirement is the film must contain as an important part of its storytelling at least a five-beat causal chain in which characters respond in rapid succession to one another’s actions. And the more general requirement is “the production should demonstrate an understanding of and a mastery of storytelling conventions relevant to the short fiction film, as well as an ability to identify and to resolve storytelling problems in a manner relevant to the art form”. This is a reminder that students should not be trying to make a miniature feature film.

Is there anything important we didn’t cover regarding short film theory and practice?

Maybe a note of honesty to close with: While the various storytelling strategies I’ve been trying to describe can be useful in helping student filmmakers avoid the most common mistakes, ultimately what counts above all else in a short film is whether or not there is magic in it. That can’t be taught. It’s something that comes in a moment of grace, if you are very lucky. So there isn’t much point in talking about it. That doesn’t mean the storytelling strategies are unimportant, but they aren’t the whole picture. And while you’re doing the hard work involved in script development, a window should be kept open for some inexplicable gust of magic to enter the room and help bring the story to life.

Big thanks to Dr. Richard Raskin for sharing his decades worth of knowledge with us and forcing us to completely rethink everything we thought we knew about the short film. If you’d like to learn more about short film theory and practice, check out Dr. Raskin’s journal, Short Film Studies, and the recommended viewing list he put together for us below.

DR. RASKIN’S RECOMMENDED VIEWING:

The War Is Over, Nina Mimica (Italy, 1997) Come, Marianne Olsen Ulrichsen (Norway, 1995) Eating Out, Pål Sletaune (Norway, 1993) Possum, Brad McGann (New Zealand, 1997) Derailment, Unni Straume (Norway, 1993) Staircase, Hanna Andersson (Sweden, 2004) Sunday, John Lawlor (Ireland, 1988)