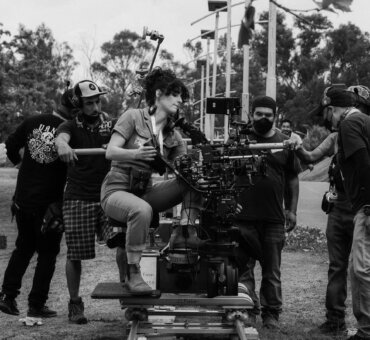

Some people know what they’re going to do with their lives before they’re old enough to drink a beer. Some of us take a little longer. Autumn Durald didn’t decide to be a director of photography until after she’d graduated college, traveled the world, and held a steady job in advertising. Once she’d made the decision, though, she didn’t look back. Since then, she’s lensed everything from major motion pictures (Palo Alto) to documentaries (Portraits of Braddock).

Autumn is convinced that taking longer to decide her career path has been a good thing. “There is a lot of benefit in doing it that way,” she says. “You live your life and you see the world and you see light in all of these different parts of the world. I had traveled across the country and all over the Middle East. All of that informs the way I frame.”

We recently talked with Autumn about education, collaboration, the importance of travel, and her lack of a “plan.”

How did you become a cinematographer?

Autumn Durald: I’ve always been a photographer. In high school I shot in black and white and developed my own stuff. So I was always interested in it. But when I went to college, I found myself more on an art history route. That became my main interest. Through that I ended up taking a film course, and I had to write a paper on Woody Allen’s Broadway Danny Rose and then a paper on Raging Bull. And the whole time I was falling in love with film. I wanted to know who was behind the camera, and I wanted to understand what a DP did because I had no idea.

After I graduated from college, I worked at art galleries and stuff, but I realized that wasn’t really my thing. So I got a job in advertising for three and a half years. It was a sales associate job. I made good money, but eventually I realized the ad world wasn’t for me either… sitting at my desk, going to meetings. So I decided to save up some money, quit my job, and spend a year learning how to become a director of photography. I started looking for ways to get on set, and the best way to do that was through film schools.

The first school I worked with was AFI, and I think my first job was scripty. I ended up loving the set experience, and I applied for film school a year later. I got in with mostly my photography portfolio. After I graduated from film school, I was lucky because a classmate of mine would recommend me for work when he was unavailable. So then I started meeting new people and that’s kind of how it all started. I decided I was going to just shoot, and I didn’t dabble in much else.

Did your background in art history affect the way you approach cinematography?

Oh yeah. Of course. Another big factor was that I was older when I went to AFI. Lots of people coming in were around 21. I was 27. I’d already traveled a lot, I’d had a real job, I’d dabbled in art history. There is a lot of benefit in doing it that way. You live your life and you see the world and you see light in all of these different parts of the world. I had traveled across the country, Europe and all over the Middle East. All of that informs the way I frame.

Do you think travel is important for cinematographers?

Definitely. It’s important to see different cultures and different faces and the way light falls in different countries. Back in the day, you could really tell where cinematographers were from. The style of an American cinematographer is not the same as the style of a Polish cinematographer. Light is unique in every country. I believe it’s important to work with people who will go to the ends of the earth to find different images and explore different textures.

I believe it’s important to work with people who will go to the ends of the earth to find different images and explore different textures.

Was there a moment after AFI when you had some sort of revelation that propelled you into doing all of this high-profile work?

It’s weird because I’m not one of those people who wanted to be a filmmaker when I was a kid, or even when I was in high school. But the moment I figured it out, after I found out what a DP does, I became so interested in it that I knew it’s what I wanted to do. And then it just came naturally. If you’re meant to be somewhere, it happens naturally. You’ll have good instincts and good taste, and you’ll find people who have similar tastes.

I did a film between my first and second year at AFI, a small feature, and that’s when I realized this is what I’m supposed to be doing. There is a lot of luck involved, but it also has to do with your persistence and the type of work you choose to put out there. You have to have a style. That’s what makes people want to work with you. If you shoot just anything, it gets muddled and you might not find your route. Now I can’t see myself doing anything else — except maybe being a farmer, just to relax.

If you’re meant to be somewhere, it happens naturally.

Is there something about cinematography that you’ve recently learned or realized?

It takes up a lot of your time. You don’t have much time for family. That’s what I’m learning. But that’s important to know. It’s one of those jobs where you go all over the place. You have to be ready to pick up and leave, and then you’re gone for months working on a movie. Another important aspect to cinematography that I’ve always believed in is trusting your instincts. The older I get and the bigger jobs I do it’s even more important. It makes for better cinematography and that’s what sets you apart from everyone else. It’s so important to know what you want and how to achieve it quickly. Have a vision and know how to guide your team in achieving that.

Are there common things that hold people back from becoming successful DPs?

One thing I saw a lot at film school — and I did this myself — was being too particular, focusing too much on making things look pretty and not on telling a story. Your work has to come from inside you. You have to have a unique perspective. What makes for amazing cinematography is when you and the director are both bringing your unique perspectives when you work together. Sometimes these young DPs — especially with digital cameras — try too hard to make things look perfect, and they don’t consider the story. Everything is starting to look the same.

You have to put yourself into the work, you have to have confidence and not be insecure. The same is true for directors. The best directors are the ones that put everything out there, and you feel it when you watch their work. My advice is to try anything, don’t be afraid to make mistakes. That’s how you learn what you like and don’t like.

Has your idea about what is “good cinematography” changed over time?

Totally. I’ve always been inspired by amazing cinematographer/director collaborations. Like Woody Allen and Gordon Willis. Together they made amazing work: good cinematography, good storytelling, good filmmaking. I always knew that, but I didn’t always understand it. There’s something within collaboration that is very important. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized it’s the most important thing. You aren’t the only one making the film. It’s a team. And everyone has to be on the same page.

There’s something within collaboration that is very important. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized it’s the most important thing.

The chemistry between you and the director is the most important thing?

Yeah. When you’re younger, you think, Oh, I can make this look good no matter what. I got this. But what you eventually realize is, if you’re going to make anything great, it takes more than a single person.

Is there a piece of advice you’ve gotten that has stuck with you?

More than a piece of advice, it’s the experience and relationships I’ve been fortunate to have with certain DPs. Early on, I had the ear of Bill Pope who shot The Matrix and many other films. I’ve hit him up for advice and spent time on his set watching him work, seeing his attitude. He’s been doing this for a really long time, and he’s an inspiration. He’s the one who made me think about the importance of collaboration. About not being the loudest person on set. Yelling doesn’t get you anywhere.

Also, I’ve always been someone who works from the inside. If I don’t believe it when I look through the eyepiece — if it doesn’t feel natural or real — how is the audience going to believe it? I know it sounds cliché but it’s true. As the photographer or cameraperson, you have to believe it and be inspired by it.

You’ve ended up intersecting with such big-name people. Was that part of your plan? Do you have a plan?

No. No plan. I guess it’s like, you decide you want to be something, you take it seriously, you find out you’re good at it, and then you just go get it. Any opportunity that comes your way, you take it. A lot of free work came my way at the beginning. Always be open to that. Meet new people. Don’t be lazy. Say yes. People always call at the last minute, so you need to be flexible. It’s a lot of hard work, so I definitely wouldn’t say it comes easy. But that’s how you grow. Pretty soon people start recommending you. You go from there.

It’s never too late to decide what you want to do with your life. But once you decide, go at it with everything you’ve got. Like Autumn said, when it’s right, it will happen naturally. Keep an eye out for Autum’s latest film, One & Two. It hits Video On Demand August 14th.